Dutch Goose Hunting: Conservation, Avian Flu and Control

Defending Dutch Goose Hunting: A Hunting Conservationist’s Rebuttal

Dutch goose hunting critics often paint it as needless cruelty, but the reality is that Dutch goose hunting is a pragmatic response to a very real, man-made wildlife crisis. The Netherlands faces an overpopulation of wild geese on an unprecedented scale – a situation created by human activity and policy. Left unchecked, this goose population boom is causing significant ecological and economic damage, endangering public safety, and even raising the risk of avian influenza in the Netherlands and beyond. In this rebuttal, a conservationist perspective is offered: regulated goose hunts are not only defensible but necessary as a form of goose population control and conservation through hunting.

The Backstory: GetDucks.com Netherlands Goose Hunting Trips Ruffle Dutch Feathers

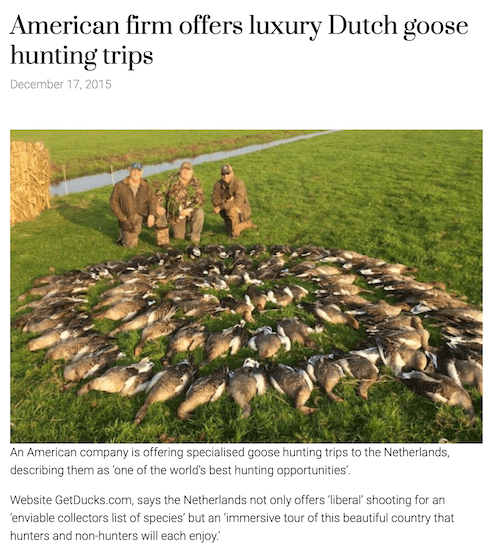

In December 2015, all hell broke loose at GetDucks HQ. It began at 2 AM Mississippi-time (9 AM Amsterdam time). Surly, fast-talking, self-important Dutch reporters with heavy accents were on the other end of the call. Skipping standard perfunctory telephone pleasantries altogether–to include introductions–they bluntly demanded in almost unintelligible “English” instantaneous explanations for “shooting ‘der geese.” By lunch that day, DutchNews.nl had published an article entitled American firm offers luxury Dutch goose hunting trips, painting a sensational picture of American hunters flocking to the Netherlands for “one of the world’s best hunting opportunities.”

Other local and national “news” rags joined in (such as Americans ruffle feathers with unlimited trophy goose hunting trips to Netherlands). The articles highlights promotional language from US outfitter Ramsey Russell’s GetDucks.com boasting of “‘liberal’ shooting for an ‘enviable collectors list of species’” and an “immersive tour of this beautiful country” for hunting clients . Emphasis was placed on the $4,600 price tag for a five-day “luxury” goose hunt package, framing it as trophy tourism exploitation. The articles oftentimes noted that Dutch law technically allows foreigners to hunt if hosted by a Dutch license-holders, implying that “Dutch hunting legislation allows foreign nationals to go on ‘trophy hunts.’” A Dutch Labour MP, Henk Leenders, even raised parliamentary questions, signaling political unease with the idea of wealthy Americans shooting local geese for sport.

To drive home the highly inflammatory “trophy hunting” narrative, DutchNews.nl quoted testimonials of American hunters proudly reporting big goose hauls: “We got 42 barnacle geese … during two morning hunts,” one client wrote, alongside a photo of piled birds. Another bragged, “I think we took 40 geese on the opening day… We’re going back – pencil us in for next August” . These anecdotes, paired with the article’s tone, suggested outrage: the image of foreigners reveling in mass kills of Dutch geese purely for fun. The implication was clear – the Dutch public is meant to see this as a gaudy, gratuitous “trophy hunt” enterprise deserving of scrutiny or scorn.

Whether fearing political reprisals or simply lacking testicular fortitude, even the Royal Dutch Hunters Association–that supposedly champions hunting in Holland–quickly chose sides. Altogether forgetting our previously cordial emails regarding hunting laws in Netherlands, condemning our use of the word “trophy,” and criticizing our goose hunting in Holland altogether, they all the while phished for local names to feed to the jackals while, of course, politically ingratiating themselves to the anti-hunting influences causing the stir in the first place.

But singularly focusing on “luxury hunting trips” and dramatic kill counts misses a critical point entirely: why are there so many geese to be hunted in the Netherlands in the first place? And is a visitor paying to hunt a goose meaningfully different from a Dutch official paying to cull one?! The Dutch media sensationally presented the what – affluent outsiders shooting geese – but pointedly ignored the context making such hunts possible, if not downright practical. To truly evaluate organized Netherlands goose hunting’s merits, one must first understand the man-made wildlife crisis unfolding in Dutch polders and pastures.

Like most contemporary, corporate-media sources, Dutch news outlets wanted only a sensationalized, click-bait worthy perversion of reality conforming to the biased narrative for whom they are indebted and exist solely as a paid megaphone. Offered a written statement under the legally binding terms that it might only be printed in its entirety and word-for-word verbatim–to include perfect Dutch translations–all major news outlets declined my offer without reply. Their silence was deafening. Cowards are like that, huh?

So here’s the rebuttal. Sssshhhh. Don’t tell anyone. See, it’s like a dirty little Dutch secret: the Netherlands is the world’s poster boy for governmental mismanagement of wildlife resources. They assent instead to the emotionally fueled, scientifically unfounded reasonings of a same-the-world-over, vocal minority despite the ultimate consequences. But their country, their business, right? No. Because many geese are migratory, the deleterious effects are far reaching. As such, the remainder of the wildlife- and bird-loving world should take note–and maybe even hold the Netherlands morally–if not financially–accountable for spreading Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza. You can’t make this stuff up.

For Context: How Dutch Anti Hunters Harass Legal Hunters with Near Impunity

A Man-Made Goose Overpopulation Crisis in the Netherlands

Far from being a pristine wilderness where thrill-seekers shoot the last remaining of a species, the Netherlands today is grappling with an overpopulation of wild geese – a problem largely of human making. Acquiescing to anti-hunters emotional rhetoric, goose hunting was banned about 2005. In the decades since, the Dutch landscape and left-leaning policies have effectively turned the country into “the most popular place in Europe for geese.” Intensive farming, with its endless acres of nutrient-rich grass and crops, combined with the Netherlands’ mild, temperate climate, and abundance of waterbodies have created an ideal year-round goose habitat. As one Dutch ecologist noted, “in the 1970s the goose was a rare animal” in Holland – hunting was essentially banned and geese were shielded by European regulations. Those protections worked too well. By leaving geese with abundant food and no natural predators or hunting, the population exploded.

This growth isn’t from migratory flocks only. Many goose species that once only passed through or wintered in the Netherlands now stay year-round and breed. For example, an estimated 600,000 “summer geese” (resident goose populations) now live in the Netherlands year-round instead of migrating away. Generous protection policies in past decades, such as hunting restrictions, allowed geese to build up large populations. Ironically, a conservation success in increasing goose numbers has backfired into an overpopulation crisis. By the mid-2010s, even Dutch wildlife groups and authorities recognized that the goose population had grown beyond sustainable levels (click here to read “Dutch Paradise for Geese” PDF). In 2013 the government announced it aimed to reduce goose numbers to their 2005 levels, which experts said would require culling about 500,000 geese . This acknowledgment – coming from a country known for progressive wildlife management – underscores that the goose boom is a direct consequence of human-altered habitat and now demands human intervention. No wonder Dutch authorities began issuing depredation permits and we were asked by locals to bring savvy American hunters!

The numbers speak for themselves. Dutch goose numbers have skyrocketed. More than 500,000 geese reside in the Netherlands during summer, and around 2.5 million migrate through or overwinter there – a 95% increase since the 1960s . What was once a seasonal migratory stopover has become a year-round goose haven. Sovon, the Dutch ornithology center, calls the Netherlands “very suitable for them,” with grassy road medians and farm fields offering “small pieces of nature… away from predators” where geese thrive.

Learn more: Sovon Goose Population Data

Public Safety, Crop Damage, and Goose Hazards

An overabundance of geese isn’t just a trivial nuisance; it creates serious public safety hazards and environmental impacts. Unchecked goose populations in the Netherlands lead to:

• Ecological and Agricultural Damage: This goose population boom brings serious consequences. Flocks of greylag, barnacle, and white-fronted geese decimate pastures and crop fields, causing tens of millions of euros in damage each year. In fact, the Dutch government spends “tens of millions of euros” annually compensating farmers for goose-inflicted losses. In just the first six months of 2016, Dutch farmers were paid €16.3 million ($18.6 million) for wildlife damage – with geese by far the top culprits (e.g. €6.5m or $7.4 million in claims from greylag geese alone). Taxpayers foot this enormous bill via the Faunafonds compensation system, an independent body that deals with provinding compensation for damage to agricultural crops and predation of livestock by wildlife. Taxpayer dollars are also spent the foolish notion that leasing agricultural cropland sanctuaries “for the geese” will somehow prevent them from depredating nearby farm crops. In reality it only increases reproductive success of geese. Learn More: Comparing Wildlife Damages in Netherlands.

• Public Safety Risks: Geese are not just eating grass – they are literally getting in people’s way. Large gaggles loiter on airport lands and even along highways. Near Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, geese pose a well-recognized aviation hazard, risking bird strikes with planes. Due to the sheer size of the goose population due to land-use practices, there’s a real danger that they’ll fly into an airplane engine one day and cause disaster. Hundreds of geese near runways have prompted authorities to seek permission to gas them for safety. On roads, drivers in Gelderland have been warned after multiple collisions with geese; the birds graze and nest along motorways where foxes won’t venture, then wander onto the tarmac. What might seem a quaint wildlife sight is, in reality, a new danger for Dutch motorists and air travelers. Fasten your seatbelts and hang on!

• Disease Spread and Biosecurity: Perhaps most concerning are the frequent avian influenza outbreaks in the Netherlands, amplified by large congregations of wild geese. The Netherlands has become a hotspot for highly pathogenic avian influenza (bird flu) in Europe, with outbreaks now occurring year-round in poultry and wild birds. Dutch authorities culled over 3.7 million chickens, ducks, and turkeys during the 2021–2022 epidemic – the worst outbreak on record. Wildlife experts have noted a “striking increase in avian flu among waterfowl” in the country, to the point that bird flu has essentially become endemic in wild bird populations.

Avian Influenza in the Netherlands: A Growing International Biosecurity Threat

Geese are known carriers of bird flu and have helped spread H5N1 globally. With over 5,300 barnacle geese found dead during the 2021–2022 outbreak, the Netherlands must reduce goose density to break the disease chain.

Learn More: RIVM Bird Flu Updates

Wild geese are known vectors for avian influenza viruses, meaning they carry and spread these pathogens while often remaining asymptomatic. When millions of resident geese gather in Dutch wetlands and fields, they create ideal conditions for viruses to incubate and jump to domestic poultry or other wildlife, such as seasonally migratory birds. During the 2021–22 Dutch bird flu wave, goose species were hit hard – over 5,300 barnacle geese were found dead in the Netherlands, the highest wild bird death toll of any species, representing as much as 7% of the local barnacle goose population. Such mass mortality events not only raise conservation concerns; they also keep the virus circulating. Infected geese don’t respect borders. Each spring, migratory cohorts of barnacle geese migrate 1,800 miles from the Netherlands to Arctic breeding grounds in Russia. Then what?

If they carry avian flu, they can transport it to pristine regions thousands of miles away. Indeed, scientists have linked migratory wild birds to the spread of H5N1 avian influenza from Europe to Africa, Asia, and even North America. One study found that the 2005 H5N1 outbreak spread from Asia into Europe and Africa via an “unprecedented long-distance transport… in which wild migratory ducks, geese and swans were implicated.” In 2021, a similar pattern occurred when a strain of H5N1 made its way from Europe to North America, likely ferried by wild waterfowl.

Global Implications: Dutch Goose Mismanagement

The Netherlands must be held accountable for managing this threat at its source. Simply put, if the Netherlands fails to control its goose problem, the rest of the world pays the price in potential pandemics and economic losses.

So the Netherlands’ goose problem is no longer a local nuisance—it’s a global issue. Infected geese migrate across Europe, Asia, and North America, spreading harmful pathogens that threaten wildlife and poultry industries worldwide. These international consequences mean that the Netherlands’ goose overpopulation is a global biosecurity threat.

When Dutch geese carry deadly viruses abroad, they endanger poultry industries and wildlife far beyond Dutch borders. Countries worldwide are now on alert for bird flu partly because migratory birds from places like the Netherlands introduce the virus. The Netherlands must be held accountable for managing this threat at its source. Allowing goose populations to run amok is not a neutral choice; it actively undermines global efforts to control avian influenza. Responsible stewardship dictates that the Dutch government reduce wild goose densities to help break the chain of disease transmission. Simply put, if the Netherlands fails to control its goose problem, the rest of the world pays the price in potential pandemics and economic losses. This is a key reason why goose population control isn’t just about crop protection or fewer geese on the runway – it’s about international public health and fulfilling the duty to combat a virus that has become “a pandemic among… birds worldwide.” Which begs another questions borrowed from recent HPAI-related headlines–what about its transmission to humanity? Have we so quickly forgotten the Global Pandemic of 2020?!

The Netherlands reckless, emotionally fueled mismanagement has created significant goose problems of epic proportion. To say the least. Importantly, it is a problem born from human alteration of the environment and scientifically unfounded protection policies. The Netherlands geese have thrived beyond control, not because hunters like those from GetDucks.com suddenly appeared, but because for years no natural check or predation was in place. Goose hunting was largely forbidden; culling was minimal and restricted. The result? A densely populated nation that’s only half the size of South Carolina is home to 17 million people now hosts an even larger population of wild geese. By 2013, the Dutch government itself acknowledged the crisis, announcing a goal to cut goose numbers back to 2005 (pre goose hunting ban) levels – a reduction requiring the culling of about 500,000 geese. Key word: culling. In other words, even Dutch experts agree that half a million fewer geese are needed to somewhat restore ecological balance. The question facing the Netherlands is not whether geese will be killed to achieve this, but how–and by whom.

Cull versus Conservation definitions (per Merriam-Webster Dictionary):

Cull (verb)

ˈkəl

: to reduce or control the size of (something, such as a herd) by removal (as by hunting or slaughter)Conservation (noun)

con·ser·va·tion ˌkän(t)-sər-ˈvā-shən

: a careful preservation and protection of something. especially: planned management of a natural resource to prevent exploitation, destruction, or neglect

Conservation Through Hunting: A Responsible Solution

Hunting vs. Culling: Conservation Through Hunting or Just “Trophy” Fun?

Critics of the American “goose safari” trips deride them as “trophy hunting” – implying they are cruel, ego-driven outings detached from conservation. Yet this perspective is profoundly disconnected from on-the-ground reality. When a species’ population is far above the land’s carrying capacity, population control is conservation. Conservation as “wise use” is taught universally in accredited wildlife management universities. Key word: use. As in consumptive use–similarly to agricultural crops, timber, cattle–and wildlife. Controlled hunting is simply one method of achieving that goal – arguably a far more sustainable and ethical method than the alternatives the Dutch government currently employs.

Consider what is already happening to manage goose overpopulation in the Netherlands: each year, government-hired cullers kill around 400,000 geese in an attempt to curb the population. These are not sport hunters seeking a trophy for the wall; they are pest controllers under contract, whose grim task is often to round up geese in bulk and exterminate them (sometimes by gassing) to meet cull quotas. Shockingly, most of these culled geese are then discarded like trash – “often being sent to factories and ground into pet food,” as NPR supposedly reported of the Dutch goose culling program–so the birds killed for crop protection often literally go to the dogs (or cats). Who else wonders which Dutch businesses and politicians cut deals in smoke-filled, back rooms to profit from this meat source conveniently garnered at taxpayer expense? European regulations may have historically prohibited selling wild goose meat for human consumption because they were once rare, but “wild game markets” now abound and wild, hunter-harvested goose breasts are especially popular during the holidays. But the current state of affairs remain: hundreds of thousands of geese indiscriminately destroyed at taxpayer expense, their carcasses largely wasted, and yet their numbers still rebounding year after year.

Read: Goose Exterminator of the Netherlands

As compared to a regulated hunting scenario, visiting hunters–under strictly licensed provisions–shoot geese which in turn at least temporarily reduces the crop-raiding population. Ask the farmers how best to chase geese off their fields. That’s right. Hunting-related disturbances. Hunters pay for the privilege – injecting money into the local economy (guides, leases, lodging, food, permits) – and very likely will eat the goose or donate it for consumption, since hunters abhor wasting game. Remember: “wise use.” Geese are removed from the population without government or taxpayer expense, and in fact with an economic gain. This is conservation through hunting in a nutshell–using hunting as a tool to maintain wildlife populations at healthy levels, while funding conservation or local communities through hunting revenues. It is the same principle by which deer hunting maintains stable deer herds in many countries, or how licensed waterfowl hunters throughout the US fund wetland conservation via duck stamp programs. In North America, waterfowl hunting annually generates over $25o Billion economic activity, which stimulates local economies and funds the most successful continental, ecosystem management plan on earth! In the Dutch context, allowing some controlled goose hunting isn’t introducing cruelty – it’s tapping into a tried-and-true wildlife management strategy that also happens to offset public costs.

Learn More: Strict Requirements to Legally Hunt and Possess Firearms in the Netherlands

Eight hundred seventy-one hunters – not per year, but in total up to that point – versus 400,000 geese culled per year by the government. Clearly, blaming population woes on “trophy hunters” is absurd when those hunters comprise a tiny fraction of the wasteful lethal management already underway!

Even the term “trophy hunt” is misappropriated. Nobody eats wall-mounted trophies, but goose hunters–and a growing number of Dutch citizens–certainly eat geese. The American hunters in question are primarily shooting common “resident” species (greylag, barnacle, Canada, and Egyptian geese) for sport and meat, not endangered rarities. Yes, they enjoy the challenge and may take photos with a pile of birds–so what–but fundamentally these geese are part of a harvest that needs to happen. That must happen. One could argue that Americans are essentially volunteering – and paying – to do a job the Dutch government is already doing in far larger numbers. In one winter 2010/2011 alone, Dutch officials killed 187,000 geese (mostly greylags) as culls, yet “this has not reduced their numbers,” according to bird experts . Against that backdrop, the perhaps few thousand geese foreign hunters might shoot in a season is a drop in the bucket. In fact, by 2016 only 871 foreign hunters had ever made use of the legal provision to hunt geese/ducks as a guest in the Netherlands. Eight hundred seventy-one hunters – not per year, but in total up to that point – versus 400,000 geese culled per year by the government. Clearly, blaming Netherlands goose woes on “trophy hunters” is absurd when those hunters comprise only a tiny fraction of the wasteful lethal management already underway. Most likely, it’s political smoke-and-mirrors deflecting their own management shortcomings to avoid being held accountable to Dutch taxpayers. And to the world.

Crucially, regulated hunting is selective and humane compared to certain mass culling methods. A hunter typically targets a flying goose with a shotgun; if successful, the kill is usually near-instant. Contrast that with gassing operations, where geese are rounded up (often during molting period when they can’t fly) and exposed to carbon dioxide en masse, which has been criticized as causing stress and suffering to the birds. Even some Dutch animal welfare advocates who dislike hunting may find gassing tens of thousands of geese an unpleasant solution? Yet the European Commission has explicitly “given the green light” for the Netherlands to gas hundreds of thousands of geese across the country as a population control measure. If that is considered an acceptable tool to protect crops and airplanes, how can one argue with a straight face that an individual hunter shooting a goose is somehow beyond the pale? The hypocrisy is glaring.

International hunters are not the cause of the goose overabundance – they are a symptom of it, arriving precisely because a man-made overabundance due to Dutch mismanagement exists.

It becomes evident that what the Dutch media framed as a decadent hobby (“unlimited” goose shooting for rich Americans ) is in truth closely aligned with the science of wildlife management. International hunters are not the cause of the goose overabundance – they are a symptom of it, arriving precisely because a man-made overabundance due to mismanagement exists. And in a small way, they are helping to mitigate the problem by harvesting some geese that would otherwise be killed anyway by Dutch agencies. Demonizing these hunters as cruel “trophy” seekers is a convenient emotional appeal, but it ignores the real cruelty of letting geese overpopulate to the point of starvation, or killing them en masse only to throw them away. It ignores the economic burden of centuries-old dairy farms, poultry producers, and Dutch taxpayers. It disregards the countless birds lost by spreading HPAI from Netherlands to the Arctic. It is the reckless mismanagement of a natural resource. Managed hunting and culling are two sides of the same coin, except one is done by willing participants who cherish the animals hunted, utilize the meat (and often the skins and feathers), while the other is an atrocious bureaucratic cleanup operation. From a conservation perspective, the former can be a valuable tool. If properly regulated, hunting is sustainable and even beneficial for managing species like geese.

From Pests to Plate: The Cultural and Culinary Value of Wild Geese

Dutch geese have significant cultural and monetary values

One aspect conspicuously missing from “trophy hunt” outrage is what happens to the geese after they’re shot. Various Dutch media portrayals assume it’s all for show. In reality, a wild goose taken by a hunter is not wasted – in fact, around the world goose is a traditional game meat. The Netherlands itself has a rich (if somewhat forgotten) history of consuming goose. The Twentse landgans (Twente goose), for example, is a heritage domestic breed from the Twente region, once kept in great numbers. Over 100,000 Twente geese were being raised in 1900, suggesting how common goose husbandry and goose meals were in Dutch rural life. By 2011, however, only 110 of that breed remained – a stark indicator that goose husbandry (and by extension, goose cuisine) had all but died out in modern Holland. This decline was no doubt influenced by the mid-20th century rarity of wild geese; as geese became less common, the Dutch stopped seeing them as food. As one Dutch citizen recalled, “for the past 50 years, it has not been normal to eat the goose in Holland because in the 1970s the goose was a rare animal” . In other words, until recently an entire generation grew up without roast goose, smoked goose breast, or goose stew on the dinner table. Nowadays, game shot by Dutch hunters is widely available; are especially popular during the holiday season. Hunter-harvested, wild goose-breast filets fetch €8.95 ($10). That’s €8.95 ($10) per goose! Now do the simple math on economic value of culled geese converted instead to pet food.

Wild Dutch goose meat is lean, organic, and locally sourced – qualities that align perfectly with farm-to-table sustainability values.

Now that geese are anything but rare, there’s a growing movement in the Netherlands to bring wild goose back to the menu – a direct counterpoint to the idea that hunts are only about trophies. Innovative chefs, hunters, and even artists have started to highlight the culinary potential of these birds. A Dutch initiative called “The Kitchen of the Unwanted Animal” (De Keuken van het Ongenodigde Dier) set out to use meat from culled animals that are considered pests. Its Dutch founders were appalled that so many Amsterdam-area geese were being killed and “wasted” each year. In response, they developed a now-famous product: Schiphol Goose Croquettes, turning the byproduct of airport culls into a deep-fried delicacy . “These animals can be delicious, and shouldn’t be wasted,” Hagenouw insists – and the popularity of their goose croquettes proved him right. What started as an art project stew pot has blossomed into a niche food trend: goose meat bitterballen, smoked goose fillets, goose sausages and more, sold at local butchers and food stalls. One Dutch smokehouse proudly offers “Gerookte borst van Schipholgans” – smoked breast of Schiphol goose – touting it as a “unique delicacy” that’s “almost impossible to get in the Netherlands” due to its limited supply. Diners who try these wild goose products often come away surprised at how rich and flavorful this free-range game bird is.

A goose cuisine renaissance underscores an important principle: Hunting can be entirely consistent with sustainable use of wildlife. Rather than mass-slaughtering geese and dumping them in landfills, the Dutch are possibly relearning how to respect the animal by using it fully – feathers to fertilizer, meat to meals.

A goose cuisine renaissance underscores an important principle: Hunting can be entirely consistent with sustainable use of wildlife. Rather than mass-slaughtering geese and dumping them in landfills (or into pet food factories), the Dutch are possibly relearning how to respect the animal by using it fully – feathers to fertilizer, meat to meals. Wild goose meat is lean, organic, and locally sourced – qualities that align perfectly with farm-to-table sustainability values. Every goose taken by a hunter for consumption is one less factory-farmed chicken or imported beefsteak that needs to be produced. In this way, sustainable hunting in the Netherlands can help fill a gastronomic niche as well as an ecological one. Historically, countries like Poland and Germany have longstanding traditions of wild goose dishes (goose Christmas dinners, smoked goose, pâtés, etc.), and the Netherlands is catching up by reviving its own. What’s more, when hunters know that the geese they harvest will be eaten and appreciated, it reinforces the ethic of the hunt as a responsible, even honorable, endeavor – the opposite of the wasteful “trophy” caricature. A bird in the hand can be food on the table. But hunting them is bad?

Hunting as a Sustainable Conservation Strategy

Goose Hunters Do the Work While Critics Caricature

It is easy for onlookers to sneer at a photo of grinning Americans surrounded by dead geese and label it “wrong.” It is harder, but far more constructive, to ask what solution those critics propose instead. The Dutch anti-hunting voices–and those that go along with it because silence is complicity–who are so quick to condemn “luxury” goose hunts have offered virtually no alternatives for solving the underlying crisis of goose population control. They’re certainly not putting their hands in their own pockets to offset the substantial financial losses experienced by family-owned-for-centuries dairy farmers. Neither are they accepting responsibility for transmission of HPAI outbreaks at home and around the world caused by their mismanagements. Do they suggest ending the culls altogether? That would swiftly lead to even more ecological damage and likely mass starvation of geese when food runs short – a cruel outcome. Do they suggest non-lethal methods like relocation or birth control for geese? Such ideas are at best experimental, and at worst fanciful, given the scale (millions of wild birds on the wing). The uncomfortable truth is that some form of harvests are inevitable if the Netherlands is to reduce goose numbers by the hundreds of thousands as its own experts recommend. And if geese must be killed, then why vilify those who are willing to do it ethically, under license, and at their own expense?

The hypocrisy becomes apparent: opponents of hunting bristle–at least publicly–at the notion of a person deriving enjoyment from shooting a goose, yet they seem relatively unbothered by the same goose being gassed in a container or silently culled by a government sniper. The end result for the goose is no different – actually, the hunted goose perhaps lived a more natural life and died quicker than one corralled for gassing. The outrage is centered not on the act of killing the animal, but on who is doing it and why. A paying hunter in camouflage is judged more harshly than a contracted pest controller, even though both are ultimately achieving the same conservation aim of reducing an overabundant population. This is a distinction without a difference. It suggests the critics are driven more by emotion and optics than by concern for pragmatic conservation or animal welfare. After all, the real-world conservation impact of a regulated hunt is identical or better than a cull: one less goose competing for resources and ruining a farmer’s field, and potentially a useful carcass rather than a wasted one.

Meanwhile, who is funding and performing the hard work of wildlife management? In the Netherlands, it is largely the government (with public funds) and a dwindling, demoralized hunting community. Dutch provincial authorities and farmers have crafted “geese management” plans that include trained hunters to keep numbers in check. It’s telling that State Secretary Martijn van Dam’s own response to the trophy hunt controversy was not to ban goose hunting outright, but to ensure it’s done with “a concrete purpose such as removing a hazard to aircraft.” In other words, even the Dutch government concedes that targeted hunting has its place when it serves a legitimate purpose like safety or crop protection. The foreign hunters maligned in the press were serving such a purpose – they targeted species identified as agricultural and aviation pests under the supervision of Dutch guides. If anything, these hunters brought extra resources to help a cause that the Netherlands was already struggling with the failed “Ganzen-7” plan when stakeholders couldn’t agree on how to cull enough geese. It is quite ludicrous for comfortable commentators to cry foul about “American trophy hunters” when those hunters have arguably contributed more to real conservation on Dutch soil – in terms of time, money, and labor – than any of the armchair activists tweeting their disapproval.

In the final analysis, the debate over Dutch goose hunting is not really about Americans, money, or trophies at all. It is about whether responsible, science-based wildlife management is embraced—or will continue to be rejected for superficial perceptions? The geese cannot be argued into reproducing less or migrating elsewhere; responsible actions must be taken. Those who understand conservation recognize that hunting is a legitimate tool in the toolkit – one that, if well-managed, reduces overpopulation, mitigates human-wildlife conflict, and even generates economic value from a problem. Those who only see a “luxury goose kill” are missing the forest for the trees.

Goose Hunting in Netherlands: the Bottom Line

Hunting in the Netherlands is helping to restore ecological balance, not upset it. It is the hunters, both Dutch and foreign, who are out in the wetlands and farmlands at dawn, in the cold and mud, doing the work necessary to keep goose numbers manageable. It is the hunting licenses, permits, and yes, tourism dollars that bring in funding – or at least offset costs – for wildlife management and habitat efforts. And it is forward-thinking hunters and chefs who ensure that a harvested goose can become a tasty meal, a source of cultural revival, instead of pet food. Or worse, a wasted life. In contrast, the loudest anti-hunting critics offer little beyond moral indignation. They neither compensate the farmers for lost income nor present a viable plan to prevent geese from overrunning Dutch green spaces. So why do Dutch politicians assent to such childishness?

The father of wildlife management, Aldo Leopold, once opined, “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” Conservation is measured in results, not rhetoric. On that score, the contribution of regulated goose hunting is positive. Every goose taken legally is one small step toward the long-term harmony between Dutch agriculture, public safety, and wildlife. Rather than malign those who participate in sustainable hunting, might the Netherlands do better to embrace all hunters as partners in conservation – holding them to high standards, of course, but valuing the role they play?

The true legacy of conservation is not written by those who object from the sidelines, but by those willing to engage directly with managing nature. In those regards, the Dutch have failed miserably and should be held morally if not financially accountable. As the saga of the Dutch geese shows, sometimes the responsible hunter and the dedicated conservationist are one and the same. The sooner we flip the script and recognize that fact, the sooner pragmatic solutions – like controlled goose hunting in Holland – can proceed without false stigma, to the benefit of all: farmers, taxpayers, tourists, ecosystems, and yes, even the geese themselves.

.

Sources: DutchNews.nl; Leeuwarder Courant; NL Times; Sovon (Dutch Centre for Field Ornithology); The Guardian; NRC; European Commission; NPR (The Salt); Dutch government publications (and others online), many others, personal observations and experiences