Preceding the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act, duck hunting was not considered recreational. It was big business. Very big. Who was Florine “Pie” Champagne and how’d he start hunting ducks commercially? What was his daily quota, how’d he hunt and where’d all those ducks go? Where’d he get decoys and calls, and how big was his spread? What firearms did he favor and just how good were his shooting skills? What became of Pie after market hunting? And why does he remain Louisiana’s most famous market hunter? In today’s Duck Season Somewhere podcast episode, grandson Benny Broussard borrows from his own boyhood memories, his mother’s meticulous notes and his uncle’s supper table stories to describe his famous duck hunting grandfather, portraying the people and culture of last-century Louisiana duck hunting “hired guns”.

Louisiana’s Most Famous Market Hunter Related Links:

Lake Arthur Marksman Gains Notoriety

Florine Pie Champagne, Louisiana’s Most Famous Waterfowl Market Hunter

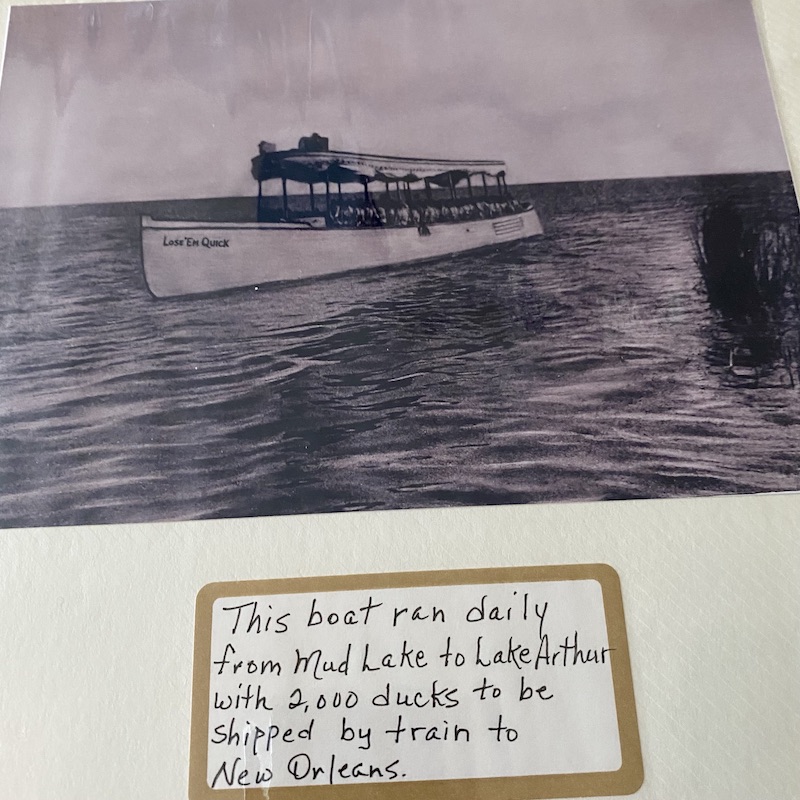

The camp was supposed to provide like two thousand ducks a day to be shipped to the French Market in New Orleans. Florine Pie Champagne’s quota was to shoot like two hundred ducks a day, which he didn’t have any problem doing.

Louisiana Market Hunting for Ducks

Ramsey Russell: Welcome back to Duck Season Somewhere. Ladies and gentlemen, this is going to tickle y’all’s fancies. Just imagine, if you will, way back when—late 1700’s, early 1800’s—when the first French Canadians were shoved off the ships and onto the shores of south Louisiana. Some of the descriptions from way back then were of clouds of ducks that obliterated the sunshine from view. As the train tracks got built and the country had to be fed, all of a sudden there’s a way to ship wildlife to the market. You got to understand: back in the late 1800’s, early 1900’s, wildlife wasn’t a recreational sport. It was a commodity like pine trees and cotton bolls and tomatoes and fishes. It was a commodity that was served at restaurants. Most folks were working and making a living, really working. They didn’t have time to go out and hunt, let alone recreationally, so they just went to the market, or went to the restaurants, and bought their dinner. Therein comes the market hunting era. Today’s guest is Mr. Benny Broussard. His grandfather was a man named Florine Champagne, nicknamed “Pie”—I’m going to mess this up—Champagne, is how I’m going to say it. The French pronounce it differently, and he’ll explain that. Florine Pie Champagne was the most famous Louisiana market hunter. Benny, how are you today?

Benny Broussard: Doing good. Doing good.

Ramsey Russell: Tell me, do you remember your grandfather?

Benny Broussard: Yeah, I sure do. Florine Pie Champagne, Louisiana’s most famous market hunter. He passed away when I was fifteen years old. Unfortunately, I was never able to hunt with him, but I did share some of his stories, sitting on that front porch. He used to always make fishing nets. He’d sit there making cast nets and stuff. Shared a few stories with me. Probably not as many as his son. Paul Champagne shared a lot more stories with me. I remember, especially once I started showing interest in wanting to duck hunt, then he started sharing some of the stories. I can remember him telling me the lead for every different species. He would show me with his hands how far to lead every duck, and talked a little bit about hunting. Like I said, most of the stories really came from his son Paul Champagne.

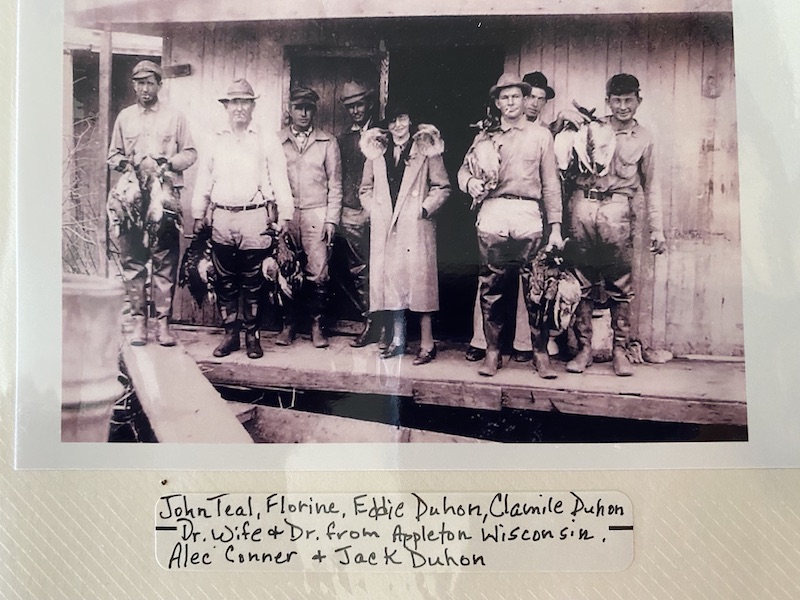

Ramsey Russell: We visited now—here in your home in Acadia Parish, Louisiana—we visited here for quite a while. You showed us some artifacts, you showed us some shotguns, you showed us some cane calls that you believe he made. Some decoys that a relative made very similar to his, some trophies and plaques. Florine Pie Champagne lived a very colorful life, didn’t he?

Benny Broussard: He sure did.

Ramsey Russell: A very accomplished life.

Where and how did Florine Pie Champagne market hunt ducks in Louisiana?

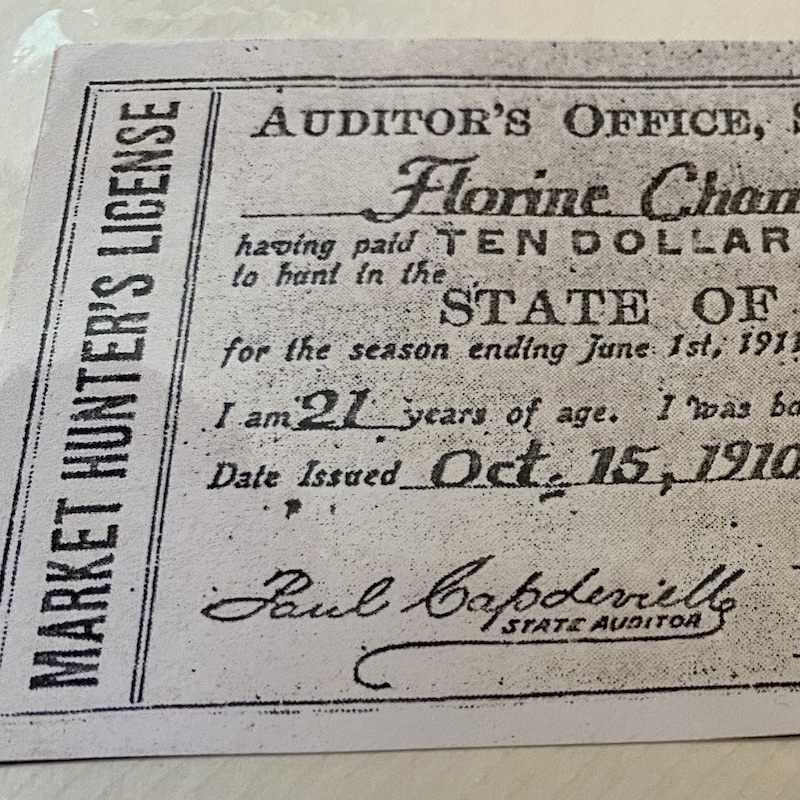

Benny Broussard: He sure did. He started out in 1906 working for the Hymel Camp. They hired him. His brothers were market hunters at that camp, and he started out kind of as a camp hand. Doing odd jobs, cleaning ducks, whatever. Then they saw he could shoot. He really had an eye, really an incredible shot. Then they let him start shooting ducks just for camp meat to provide to the camp. That was in 1906. By 1908, he was such a good shot that that’s when he really started market hunting.

Ramsey Russell: Let’s talk about this market. When you say he started market hunting, how would he market hunt? Where would he market hunt? Where on a map are we talking?

Benny Broussard: Most of this hunting was around the Lake Arthur area, around the Grand Lake area, Mallard Bay. All of those areas right there. The camp was supposed to provide like two thousand ducks a day to be shipped to the French Market in New Orleans. His quota was to shoot like two hundred ducks a day, which he didn’t have any problem doing. I’m not sure how the other hunters did it, if maybe they shot on the water or not, but he was such an excellent shot. Everything was shot on the wing. He never shot anything on the water.

Ramsey Russell: How old might he have been in 1908?

Benny Broussard: He must have been around twenty. Probably nineteen, I would think. Yeah, he was born in 1989.

Ramsey Russell: 1889.

Benny Broussard: 1889. Right.

Ramsey Russell: Man, that’s crazy times. Did you ever hear what kind of ducks they shot?

Benny Broussard: From what I understand, what the people were asking for was mallards, pintails, and teals. I think canvasbacks, too. I saw somewhere, it’s written down, where they would get like 50¢ a pair for the mallards.

What guns were used by Florine Pie Champagne while market hunting ducks in Louisiana?

He was so good of a shot that he knew just how to lead him, where he’d shoot him in the head. He’d actually get upset, when he found BBs in his ducks that were shot in the body.

Ramsey Russell: They weren’t punt gunning, like you hear in them stories about the market gunning down here, they were out there with Model 12, 12-gauges?

Benny Broussard: Right. He probably started out with a Winchester Model 1897 and then, later on, went to the Model 12. But, yeah, everything was shot in the wing. He was an incredible shot. They said he very seldom missed a duck. I even heard stories where—he understood that you were providing meat for a market, so he didn’t want them to be all shot up with BB holes everywhere. He was so good of a shot that he knew just how to lead him, where he’d shoot him in the head. He’d actually get upset, when he found BBs in his ducks that were shot in the body. Just an incredible shot.

Ramsey Russell: Headshots only. You had told me earlier that there were times he went out without a shotgun and used a .22 rifle.

Benny Broussard: Right. He was so good, he could actually shoot ducks out of the air—geese, anything—with a .22 rifle. He had a Winchester rifle.

What was it like growing up the daughter of a Louisiana market hunter?

The family would eat the gizzards and hearts and livers and stuff like that. She said she remembered going down to the water to clean the gizzards, and the catfish would just suck them right out of her hands.

Ramsey Russell: How does your mama describe growing up the daughter of a market hunter in southwest Louisiana, back in those days?

Benny Broussard: She was very proud of her dad. They had to live wherever he worked. Sometimes they lived in houseboats, sometimes at Mallard Bay, where her mother’s family had owned that property. Then at one point, after market hunting, he guided for the Coastal Club. They actually lived out there at the Coastal Club. Her and my grandmother had to clean ducks. They did all the camp chores. I think my grandmother had sisters that also worked at the camp. Some of her brothers were hunters at the camp, two guides. In earlier days, they were market hunters also. She remembered that when they were guiding for sports, of course the sports would get all the ducks, and the family would eat the gizzards and hearts and livers and stuff like that. She said she remembered going down to the water to clean the gizzards, and the catfish would just suck them right out of her hands. They were so used to being fed, right there.

Ramsey Russell: Wow. Did she ever share with you any of her other memories of growing up in a market hunting camp that would characterize Florine Pie Champagne?

Benny Broussard: Mostly the day-to-day chores, what they had to do. All the keeping up with the camp, cooking for him, and different things like that.

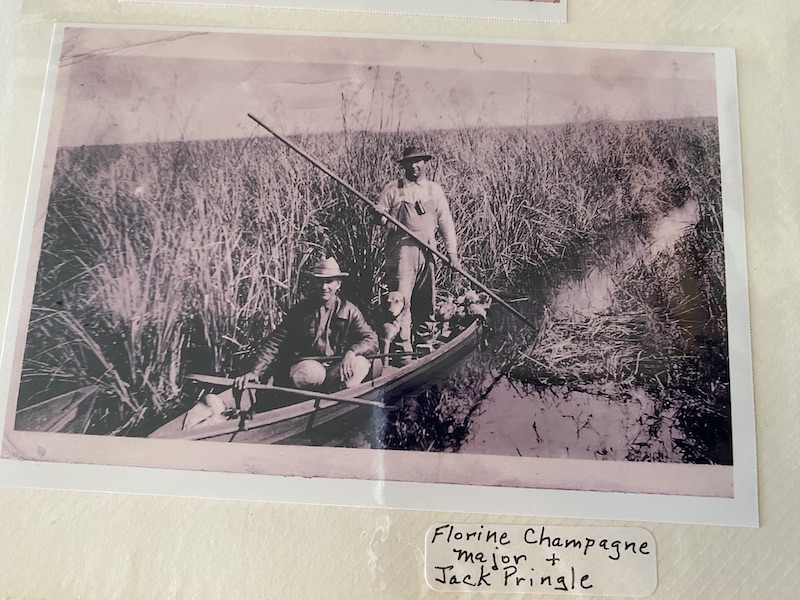

Ramsey Russell: When they were going out market hunting like that, I guess they were push-poling out? In a lot of the old black-and-white pictures—I was astounded at how many photos you had—they were using a lot of pirogues. This was way back before mechanized motors and stuff. They were push-poling out into those marshes and hunting.

Benny Broussard: Right. They very seldom used motorized boats. Sometimes they were pulled out with a motorized boat, and then they were dropped off, all the guides, they’d get in their pirogues. Yeah, it was a rough life. They had to push-pole with their decoys and all the gear and everything, then come back in with up to two hundred ducks. Just push-poling. Some of them may have had dugouts, I haven’t heard too much about the dugouts, but I know they used the pirogues quite a bit.

Ramsey Russell: You talk about coming back with two hundred ducks; you’re looking at five or six hundred pounds in the bottom of a pirogue.

Decoys used by Pie Champagne while market hunting ducks in Louisiana?

Benny Broussard: Oh yeah, I’m sure it was a load, along with the decoys. That’s pretty heavy when you’re using all handmade wooden decoys. Which he did make his own decoys, carved out.

Ramsey Russell: I guess they made decoys because you couldn’t go to the store and buy them. You used what was available. You were telling me, somebody in the family has got a couple of his decoys. You were showing us pictures of mallard decoys.

Benny Broussard: Yes.

Ramsey Russell: Can you describe those?

Benny Broussard: Yeah, what’s left. He used to have a sack full, and he’s got a pair left. They were all hand-carved.

Ramsey Russell: Out of tupelo?

Benny Broussard: Out of tupelo, right. Hand-painted everything. Of course, I’m sure it was all lead paint. We still paint it the same way.

Ramsey Russell: Back in the good old days.

Benny Broussard: Yeah.

Ramsey Russell: Probably lasted longer.

Benny Broussard: Yeah, I’m sure.

Ramsey Russell: How many decoys would you reckon he hunted over? I’m trying to think of what he would use for two hundred ducks a day.

Benny Broussard: I have never really heard anyone say, but, looking at the pictures, it looks like he had maybe three dozen. Something like that.

Ramsey Russell: I’ve hunted in parts of the world, some of these remote marshes we hunt in down in Argentina, and we’ll leave the camp—because we have to walk in a pretty good ways, or skiff in, similarly to a pirogue—and they won’t have but ten or eleven decoys. Super light, little, cheap decoys. As we shoot ducks, those are the decoys. Those dead ducks are the decoys. I would think they did something similar, back in those days.

Benny Broussard: I would think so. I saw some of the pictures—which is remarkable, that they actually had pictures from back in the day—but I saw pictures, and you can see all the dead ducks still laying on the water. They didn’t pick them up right away.

Ramsey Russell: I wonder what your granddaddy would have said to know that his decoys—his tools, carved from nature and painted with lead paint, stuck out there just to kill them ducks and make a living for his family—what he would think about the value of those decoys today. What do you think he would have said? Tell the folks how much y’all have been offered for that pair of decoys.

Benny Broussard: Yeah. I’m pretty sure he would be shocked if he knew the value of those decoys. I know one pair—when his son, Paul, owned them—someone had offered him like $18,000 for the pair. Then there’s one that we know was made in 1908 by one of his brothers, and the guy just said, “Name your price.”

Ramsey Russell: Wow. Did he name a price, or did he just keep it?

Benny Broussard: He never did come out with a price. Yeah, he kept it. My uncle kept it, and now my uncle’s son, who is my cousin, owns them now. I don’t think he wants to sell.

Ramsey Russell: I wouldn’t sell.

Benny Broussard: No.

Florine Pie Champagne’s Model 12 Winchester Shotgun and Shooting Feats

His gun, a 30-inch barrel Winchester Model 12, was not the ideal skeet gun. Nobody knew anything about Lake Arthur, Louisiana. But when the trap shoot was over, he won singles, doubles. Florine Pie Champagne walked away with everything.

Ramsey Russell: Tell everybody about this Model 12 shotgun that’s laying on the counter, here.

Benny Broussard: We looked up the serial number on it, and he had bought it in 1914. Like I say, he would have hunted with it as part of his market hunting days, but he did use it the rest of his life. That’s the only gun he ever had. It’s been shot so many times, the barrel has been changed out quite a few times. They said, also, that .22 rifle—that Winchester he had—the barrel has been changed three or four times. He shot so much. Actually, in 1924, when he was working for Jim Gardiner—the owner of the Lacassane Company in Lake Arthur—he was the head guide there, and he saw how good grandpa shot. He asked him to enter the South Zone championship in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1924. He went over there, and people were kind of laughing at him. The way he was dressed, he didn’t look like one of the sports that shot skeet. His gun, a 30-inch barrel Winchester Model 12, was not the ideal skeet gun. Nobody knew anything about Lake Arthur, Louisiana. But when the trap shoot was over, he won singles, doubles. He walked away with everything.

Ramsey Russell: Just imagine: this former market gunner who was a simple man, lived in a very rural and simple part of the world. He shows up to Atlanta. A billionaire Texas oilman had invited him to come shoot. He’s sitting there with a bunch of other extremely wealthy men that have probably got all kinds of fancy name-brand over-and-under shotguns, everything else. Here he shows up, simply-dressed, with an old, battered, 30-inch, full choke pump Winchester shotgun that he had killed gazillions of ducks with. They all kind of snickered and laughed like, “Who the heck is this rube to run among our ranks?” But he sent them all to the cleaners, didn’t he? They knew where Lake Arthur was, and who he was, the rest of their lives, didn’t they?

Benny Broussard: They knew, after that.

Ramsey Russell: That’s a heck of a trophy cup he got there, too.

Benny Broussard: Yeah. He gave the biggest one to my mother, which I have here, and one of my aunts has the other one.

Ramsey Russell: Was that just a one-time event, or did he continue to shoot like that?

Benny Broussard: Yeah, he did. He didn’t travel all over the country. He said he was a marsh man. That’s what he wanted to remain: a marsh man. He was actually recruited by Winchester and Remington to be a trick shooter, to do these shows all over the country, but he didn’t want to do that. He did enter other skeet shoots, but only the local ones. He won—I’m not sure of the year—a gold watch, solid gold watch, with his initials on it. Some other different odds and ends, he won. Kind of jumping forward, but later, after his career was kind of over as far as hunting— He hunted various camps all the way to 1936, then he got crippled pretty badly with arthritis. He later got a job as a boat captain.

Then, when he finally retired, he had heard about the Golden Oil Jubilee, the fiftieth anniversary of the oil strike in Louisiana. They had a memorial trap shoot in 1951. He had wanted to enter that contest, and his son Russell said, “Pie, you’re crippled with arthritis. You can’t even stand up anymore.” So he asked Russell to make him a stool. He showed up there, and they had offered him a practice shot because he hadn’t shot in so many years, but he refused. Then when the trap shooting started, he missed the very first bird that they threw. He missed it, and the crowd was kind of disappointed that the old man couldn’t shoot anymore.

Ramsey Russell: How old would he have been? He was an old man.

Benny Broussard: Yeah, he would have been probably in his sixties. I’m not sure. Somewhere in his sixties.

Ramsey Russell: Debilitated with severe arthritis, and his son had made a stool for him to sit on. Yet he’s out in front of God and everybody, and the first clay target he missed clean.

Benny Broussard: Yep, missed it clean.

Ramsey Russell: Then what happened?

Benny Broussard: Then after that, the second one, he powdered it. The third one, powdered. After that, he never missed again.

Ramsey Russell: Was he shooting that same Model 12?

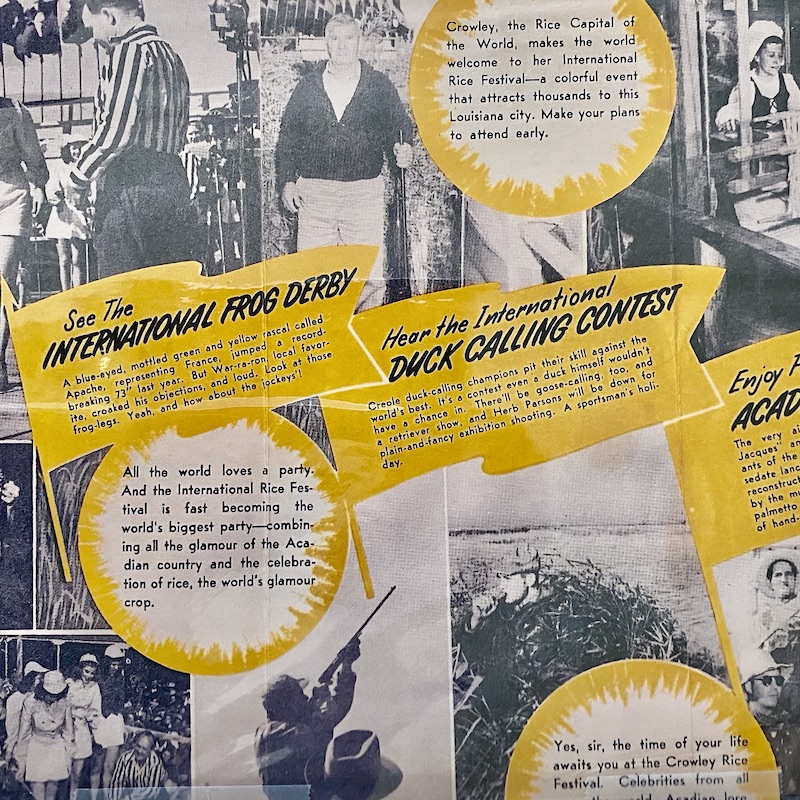

Benny Broussard: That Model 12, right there, that you see. Yeah. So he won a Remington Pump 870, which I have here. That he won in 1951. He also won another Model 12, that was in the International Rice Festival, the International Duck Calling Contest, in 1947. He won that.

Pie Champagne’s Louisiana Cane Duck Calls

Ramsey Russell: Talk about that, now, because the first thing you showed us when we walked up— Mr. Dale Bordelon’s here with me, we all know him for his handmade, completely cane duck calls—but one of the first things you showed us was a pair of cane calls that Pie made himself. He didn’t just call those ducks wild. He was a real caller. I’m assuming back in those days, 1947, they probably judged the calling by it sounding like a duck—how you’d expect a duck to sound—not by all this range of noises these professional callers make today. But he actually won a championship for calling them, didn’t he?

Benny Broussard: Right. Yeah, he sure did. He could call ducks just as good as he could shoot them.

Ramsey Russell: Do you know whether or not he entered those contests with his own calls?

Benny Broussard: Yes, it was actually the duck calls that he made himself.

Ramsey Russell: Wow. That’s unbelievable. What kind of stories did he tell you, growing up? Especially because you told me he gave you a call when you were a young man.

Benny Broussard: Yeah, he did give me a call. He showed me a little bit about duck calling, but I don’t really remember that much about the tips that he gave me. I remember he gave me a lot of pointers starting out. I regret that I wasn’t able to hunt with him, but he was crippled up so bad, by then.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act prohibited market hunting in Louisiana and elsewhere and Florine Pie Champagne became a famous Louisiana duck guide.

Ramsey Russell: Okay, so to keep up with the timeline here—we’re jumping all around his life, it’s great—but he was a Louisiana market hunter. Then the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918, and he became a duck guide. Of course, everybody wanted to hunt with him. Who, mostly, were his clients? Who were some of the people that he did guide in that phase of his life?

Benny Broussard: Yeah. After market hunting was over, he had formed his own hunting camp with two of his brothers and a friend, Three Ace Hunting Camp, that they ran for a while. Then, when he went to work for Jim Gardiner with the Lacassane Company, he brought Franklin Roosevelt duck hunting.

Ramsey Russell: Really?

Benny Broussard: Yeah, he sure did. That was before he was president, and also before he was crippled with arthritis. He was later in the wheelchair.

Ramsey Russell: Did he guide FDR?

Benny Broussard: Yes, he actually did, because he was the head duck guide there. They say people would fight over him. People wanted Pie. He also brought Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Ted Williams duck hunting. That’s the most famous people I know. I’m sure there’s a lot of other famous people.

Ramsey Russell: I was shocked—when we were looking at the old photos, there was a flyer from that 1947 World Champion Duck Calling Contest. You said that he met Kennedy?

Benny Broussard: Right. He wasn’t president at that time, but he did meet Kennedy.

Ramsey Russell: Which makes me wonder: what the heck was Kennedy doing at a 1947 duck calling contest? Maybe the man was a duck hunter we don’t know about.

Benny Broussard: Yeah, it could be. I know he had friends here in Crowley. One prominent family here in Crowley were friends with Kennedy, and still are with the family, I believe.

Ramsey Russell: He doesn’t sound, to me, to be the kind of man that was intimidated meeting up with Franklin Delano Roosevelt and taking him duck hunting.

Benny Broussard: No. I heard he also met President Taft. I don’t know the story. That’s all I know, is that he said he had met three presidents, or people that were later presidents. But I don’t know the story about Taft.

Ramsey Russell: My goodness gracious. He sure did live an interesting life, didn’t he?

Benny Broussard: Yeah, he sure did.

Family Stories About Duck Hunting with Florine Pie Champagne

A lot of times, he’d use a .22 rifle. He was such a good shot. He didn’t really need a shotgun a lot of times. He said that, one time, they were hunting at Umbrella Point with a .22, and the daily bag limit back then was ten ducks.

Ramsey Russell: What are some of the stories your uncle told you about your granddaddy? I think maybe he heard Florine Pie Champagne talk about memories of hunting back in that day. Just places he hunted or things he saw. The number of ducks, stuff like that.

Benny Broussard: Yeah, he had quite a few stories. Let’s see, one of the stories… They had brought this guy—his name was Jack Pringle, he came down every year, he was from the Alexandria area—he was dove hunting, one time, with a Model 1897 with the exposed hammer, and he grabbed the gun to pull it to him. It accidentally discharged, and he died. That was one of the stories.

Ramsey Russell: I was asking you about his last duck hunt, Benny. He commercially hunted, and then the arthritis got him. He did a little bit of competitive shooting, still, at one time. He became a boat captain. Did he continue to recreationally duck hunt with his family? Was that something he did throughout the remainder of his years?

Benny Broussard: Yes. He worked at a lot of different duck camps. Then after it was all over—once he started working as the boat captain for one of the oil companies—they were allowed to hunt on the job, so he did quite a bit of hunting. His son Paul Champagne hunted with him a lot. He brought him out there, and he continued to hunt quite a bit. Brought Paul on his first hunts. I have some stories about Uncle Paul hunting with him. He said that, a lot of times, he’d use a .22 rifle. He was such a good shot. He didn’t really need a shotgun a lot of times. He said that, one time, they were hunting at Umbrella Point with a .22, and the daily bag limit back then was ten ducks. They’d got twenty ducks on that particular hunt.

How Pie Champagne conserved shells while shooting ducks

Benny Broussard: Let’s see, he was talking about how expensive shells were during World War II. It was like $5 a box for shotgun shells, so they had to really conserve their shots. One thing that grandpa said—that he learned during market hunting days, to conserve his shells—was that when ducks were coming in, there were two times they would cross. He would watch when they were coming in, and when they would leave. He said there were always some times ducks would cross, and he’d try to get two shots. In one of his stories, he’d bring out like fifty shotgun shells, and then he killed maybe sixty-five. He just knew how to shoot.

How many ducks did Florine Pie Champagne shoot during his lifetime?

Ramsey Russell: Golly. How many ducks do you reckon he shot in his lifetime? If you had to guess.

Benny Broussard: I would think it would be maybe 100,000 because of his market hunting days. Two hundred ducks a day, with a two month season—you know, that’s a lot of ducks. Then, after that, I think the season was at twenty-five, at one time.

Ramsey Russell: Let’s say he shot 12,000 ducks per season. Maybe they were hunting—like the gentleman we talked to yesterday—they started hunting in September, when the first ducks started showing up, and didn’t stop until the last duck was gone. Now, we ain’t talking a two month season, we’re talking a five or six month season. How long did he actually market hunt?

Benny Broussard: Well, he started at that camp in 1906 as a kind of a hand, helper, whatever. Then he really, officially, started in 1908. Then it ended in 1918, so probably about ten years.

Ramsey Russell: All right. So ten years he did that. If he hit his quota of two hundred ducks a day—and I say it a lot, you got good days and bad days—but if he hit two hundred bucks a day for ten years, that’s over— If I’m doing the math right—and I’m terrible at math—that’s 120,000 ducks.

Benny Broussard: Yeah. I would believe it.

Ramsey Russell: Is that right? 200 x 60 = 12,000 x 10 years. It’s 60 days. That’s 12,000 ducks a season that were going to the market. He did that for 10 years. That’s 120,000 ducks, just while he was a market hunter.

Benny Broussard: Yeah.

Ramsey Russell: Then, after 1918, the duck limit initially was around twenty-five. It became ten much later in his life. So it could have been a quarter-million ducks minimum that Florine Pie Champagne shot over his lifetime.

Benny Broussard: It could be. Very well could be.

Ramsey Russell: Very easily could have been that. What I’ve learned in talking to some folks down here in Louisiana—like the gentleman we recorded most recently—the only seasoning, really, back in those days, was salt and pepper, down here. And cayenne. They hunted outside that. There were relationships, we learned on a former podcast, with local game wardens. So beyond the market, they just hunted. I think a quarter million ducks would be very easy to get your mind wrapped around. What other stories have you got, there?

Benny Broussard: Let’s see. He was talking about calling in geese. Back then, they would shoot a lot of Canada geese, and Grandpa would call in geese with his mouth. He said, one of the hunts, they called in five geese, and they shot five. I’m sorry, the limit was five, and they’d got nine that morning. He was saying how heavy they were. Grandpa couldn’t walk, so he had sent his son Paul. It took him three trips to bring all the geese back to the boat.

Ramsey Russell: How many children did he have?

Benny Broussard: He had five. He had two boys and three girls. My mother was the oldest girl. The only one that really hunted was Paul. Russell didn’t hunt that much. He said he taught my mother to shoot, and, at one time, she had a job where they would shoot the blackbirds out of the rice fields to scare them away.

Ramsey Russell: Growing up, did they ever hunt other birds? Like robins and stuff like that?

Benny Broussard: Probably did. I don’t remember him saying anything about the robins, but I know he did dove hunt a lot. He squirrel hunted a lot. I heard stories about him squirrel hunting along the river in Lake Arthur. I don’t know anything about deer. I never heard him talk about deer.

Ramsey Russell: I’ll bet he did a lot of duck and goose hunting down in this part of the world.

Benny Broussard: Oh, definitely, definitely.

Pie Champagne’s extraordinary wingshooting ability with .22 rifle

A .22 rifle. He was just such a good shot. Another day, there were some swallows, and this guy asked if he could hit those swallows. He shot three of them.

Ramsey Russell: Benny, what other stories have you got about your granddaddy, Florine Pie Champagne?

Benny Broussard: About him being such a good shot with a .22. One of his friends—he was also a Louisiana market hunter, Eddie Dulan—they went hunting on Lake Meziere, one day, and he shot like fifteen pintails and four ringnecks with a .22 rifle. He shot so much with that .22. He changed that barrel like two or three times.

Ramsey Russell: And they were flying, they weren’t sitting on the wall.

Benny Broussard: Yeah, he’d shoot ducks [with .22 rifle] in the air. One day, he was with one of his friends, and they just happened to see a buzzard, way up there in the sky, circling overhead. He asked Grandpa if he thought he could shoot that buzzard, and he shot it. It fell from so high, when it hit the ground it just broke in half.

Ramsey Russell: My goodness. With a .22 rifle?

Benny Broussard: A .22 rifle. He was just such a good shot. Another day, there were some swallows, and this guy asked if he could hit those swallows. He shot three of them. Later, when he was a boat captain, this guy had bet him if he could shoot— There were seagulls that would follow the boat. He asked him if he could shoot seagulls. He bet him $5, and Grandpa got up with that .22 and he just started shooting. They just kept falling and falling, and finally the guy told him, “Okay, you can stop shooting now.”

Ramsey Russell: He done got into killing mode!

Benny Broussard: Oh, yeah. That was his favorite rifle. He brought that rifle with him everywhere.

Ramsey Russell: What kind of .22 rifle was it?

Benny Broussard: It was a Winchester. I’m not sure which model it was.

Ramsey Russell: Semi-automatic?

Benny Broussard: It might have been a semi-automatic. I don’t know if they had semi-automatics back in the day, but it could have been. I’m really not sure. I don’t know. One day, one of his hands on the boat had it propped up against the wheelhouse, and he bumped into it, and it fell overboard. He was upset. That was his favorite gun.

Ramsey Russell: The bird life in south Louisiana was safer.

The time 3 Louisiana duck hunters shot 500 ducks

Benny Broussard: Yeah, for sure. Well, this wasn’t with the .22, but he had went hunting with his friend, Eddie Dulan, again, and another guy, Jim Gardiner, the one that owned the Lacassane Company. The ducks just kept coming in, rolling in, rolling in. They would shoot like twelve to fifteen, every bunch that came in. When they finished that hunt, they had like five hundred ducks stacked on the ridge.

Ramsey Russell: Two men had five hundred ducks.

Benny Broussard: Five hundred. Well, three. I think there were three. Eddie was there.

Ramsey Russell: My goodness.

Benny Broussard: They ended up giving them all to an orphanage.

What duck species did Florine Pie Champagne likely favor?

Ramsey Russell: My goodness. Did you ever hear whether or not, or have a feeling of whether or not, he was a species purist? Or did they shoot every duck that came in the decoys, or near the decoys? Like I know that in your collection, here, you got a ringneck decoy. They weren’t shooting just mallards, back in the day, and pintails and teals. They might have been shooting everything. Do you know whether or not he shot shovelers?

Benny Broussard: He probably did. I know for the market hunting days, in those days, the people had a taste just for mallards, pintails, canvasbacks, and teal. I’m sure they’re bound to have shot other species. For sure when he was guiding in all these duck camps.

Ramsey Russell: What other stories you got?

Florine Pie Champagne’s favorite retriever

Benny Broussard: He was really good at training dogs. He loved Chesapeake retrievers. His favorite dog—had a lot of different dogs over the years—but this one, this dog was very special. It was given to him by Jimmy Gardiner, the one that owned Lacassane Company. It was so good that—well, $500 today is not a lot of money, but—he was offered $500, back then. I’m not sure of the timeline, but he was offered $500. I’m sure back then it was a lot of money. The dog was so good. It just did everything he wanted it to do.

Ramsey Russell: It had a lot of experience.

Benny Broussard: A lot of experience. They had their boots stacked in the hunting camp on a bench, and the dog would go get his boots. Every morning he’d get ready to go hunt, he’d bring one boot at a time. The other guides said, “Well, we’re going to play a trick on him.” So they would hide his boots, and the dog would just go sniffing around. He’d find his boots. It didn’t matter where they hid them. He could always find his boots, and he brought them in.

Ramsey Russell: No telling how many ducks that dog fetched out of that marsh over the years.

Benny Broussard: I’m sure it was a lot. It was a lot.

Florine Pie Champagne’s very last duck hunt

Ramsey Russell: You were going to tell me something about his last duck hunt.

Benny Broussard: Yeah. Like I said, after he had retired, he had hunted mostly with his son Paul. His son Paul later married, and his father-in-law had this farm in the Thornwell area, west of Lake Arthur. His last hunt was in 1954. He was so crippled, he couldn’t walk at all, so they had brought him out there on a tractor, with a platform on the back of the tractor. That was the last hunt he ever made. Paul said he thought he had shot like three ducks. They had to help him stand up, and he’d shoot. As soon as he would shoot he would just fall, sitting down on that bench, and just bounce up in the air.

Ramsey Russell: He was tired.

Benny Broussard: He was tired. It was the last hunt he ever made.

Ramsey Russell: How many years did he live, after that last hunt?

Benny Broussard: He died in 1966, so I guess about twelve years after that. He was pretty much confined to just sitting on the porch. That’s how I remember him. He would make nets. He liked to make seines and cast nets and all that stuff. He made him for everybody in town.

Ramsey Russell: Was it like a side living, or did he just give them away?

Benny Broussard: He’d get paid for them, but it was just kind of just a little odd job. He liked to go to the bar. They’d bring him to the L A Bar in Lake Arthur. He loved playing Bourré. He was a card player. Whiskey drinker. At the duck camps, he was always the first one up in the morning, the last one to go to bed at night. He was out with the sports playing cards. Was a very hard worker in all these duck camps.

Ramsey Russell: One of the stories that somebody was telling me— I thought it was very interesting to put this all in context. A man named Fred Dudley bought ten thousand acres, down in southwest Louisiana, for 10¢ cents an acre. He hired ten old French men to market hunt, and one of them was your granddaddy. I’m assuming this—somewhere in all these stories we’ve heard from you—is where he made a lot of his living. Two hundred a day. They put them on boats—there’s a picture, in your photo album which your mama gave you, of that old boat—that would go back and forth with two thousand ducks a day, going to market. They would have them ducks in salt or ice, in these big old barrels, and off they’d go to the market. I even read somewhere that the folks back then didn’t want a whole picked duck. They wanted to see what they was getting, at some point. Some of the process would be done; they’d gut and draw them, and then later pick them.

When market hunting was prohibited with the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, Mr. Dudley feared that that land was worthless, that it just wouldn’t amount to nothing, and ended up selling it to a wealthy land speculator that, in turn, sold it to the government. It is now Lacassine National Wildlife Refuge, which is a pretty important place down here for waterfowl. To me, it’s extremely interesting that your granddaddy played a part in all that.

Growing Up the Grandson of Louisiana’s Most Famous Market Hunter

Ramsey Russell: Now here’s a question I like to ask folks, and I’m going to borrow back from a story that you told me when we were looking at your photo album. You said that when you grew up and you started duck hunting, you’d come in with ducks from hunting, and your mama didn’t want anything to do with picking them ducks.

Benny Broussard: Oh, no. No.

Ramsey Russell: My mother-in-law used to tell me about her mamaw, my wife’s grandmother. Her granddaddy would go out quail hunting, there in central Mississippi, and would come in and just lay his bird vest on the counter. Mamaw would take over picking and cleaning and doing all that with them birds. That’s just how them people were. But your mom had picked enough duck in her lifetime, hadn’t she?

Benny Broussard: Oh, yeah. She sure did. She didn’t want to pick any more ducks. Me and my dad had to pick all the ducks. Well, back then, it was just me duck hunting. My dad, after World War II, he just didn’t want to hunt anymore. I kind of got interested in duck hunting, and Grandpa Florine kind of gave me a few tips. I hunted the rice fields. I hunted before school, in the morning. Dad would work shift work, so I’d only hunt when the car was available. We only had one car, and I hunted rice fields south of Lake Arthur. We did all the duck cleaning, me and my dad. Mom didn’t want to have any part of that. She was telling me, back in the day, they made their own feather pillows, the feather mattresses, and everything. She said she remembered when she got married to my dad—his family grew up on the banks of the Mermentau River, and they had Spanish moss hanging from the trees—so their mattresses were moss mattresses. She hated those mattresses. The feather mattresses she grew up on were a lot more comfortable. That was the one thing she regretted.

Ramsey Russell: Did she ever talk about how many ducks might be required to make a feather mattress?

Benny Broussard: I don’t recall. I don’t remember how many. I’m sure it had to be a lot. I know we saved all of our duck feathers.

Ramsey Russell: Growing up, you did?

Benny Broussard: Growing up, we did. My mom was a seamstress. She was really good at sewing, so she made the casing, or whatever, for the pillows. So everybody had feather pillows. We didn’t have feather mattresses anymore, but definitely had feather pillows. I had one, and I regret— I was in the Louisiana National Guard, and I brought it to summer camp, one summer. My pillow. When they picked up our bedding at the end of the two weeks, they took my pillow. I was so upset. My mother had made it. I was really upset. I asked if I could get it back, and they sent me to this warehouse. They said, “If you can find it—” It was like a mountain of pillows. I couldn’t believe, when I opened that door. So I didn’t even bother looking for it. It was just too many. But I was upset.

Cooking and eating ducks

Ramsey Russell: Here’s what I was wanting to know: did your mama have a favorite recipe for cooking duck?

Benny Broussard: Her style of cooking ducks was just like Grandmother’s. Florine’s wife, Kate. She would pot roast ducks in a cast iron pot, and they’d brown them. I mean, really, extremely browned. She’d just cook them down.

Ramsey Russell: Made what folks down here call a gravy.

Benny Broussard: Right. Gravy.

Ramsey Russell: I’ve heard that described. Would she ever put onions and celery and peppers? Then brown them ducks and just put it in—add a little water—and just cook down. Is that the same way you cook them?

Benny Broussard: That’s the same way I cook them, but I just never mastered it like she did. I just haven’t learned how to do it.

Ramsey Russell: A mama’s cooking is always better. Did she save the hearts, and stuff like that, still?

Benny Broussard: Yeah, absolutely. When we cleaned the ducks, we had to keep the gizzards and the hearts and the livers and everything.

Ramsey Russell: I got a friend down around New Orleans—and it’s been a while since I hunted with him—but once a year, toward the end of the season, he would go out and shoot coots. I said, “Why?” He said, “My grandmother, all she wants is coot gizzards to make gumbo.” Was that a part of y’all’s growing up, too? Back in the day, I’ve heard, for a lot of folks in this part of the world, coots were a big deal. Do you reckon your granddaddy and his family, did they shoot coots or fool with them at all?

Benny Broussard: I don’t think he did. Maybe. It’s possible, but I don’t remember anything about coots. Then me, growing up—the duck camp I hunt in the marsh right now, south of Lake Arthur—my dad, like I said, he had quit hunting. But after he retired, he started hunting at this duck camp. He hunted every day of the week except Sundays. He never hunted on Sundays. But we didn’t shoot coots. I don’t know why. Today, I don’t shoot them either, because that was the way I was taught. We just didn’t shoot coots. I know a lot of the people in the area, like you say, do hunt them. I started bringing this guy from Houma—that moved here to Lafayette—with me hunting, and he sees coots in Lake Arthur, where I hunt. He always asked, after the hunt’s over, if he could shoot a few coots. So he shoots them, and I’ll shoot some and give them to him. I just wasn’t brought up shooting them. I know they like the gizzards. The gizzards are so big on them. Spoonbills, too. We kind of were brought up trying not to shoot the spoonbills, but then we realized, around here, the spoonbills that eat in these rice fields are good to eat. Nowadays, the duck hunting around here where I hunt is not like it used to be, so we’re not particular anymore. We shoot whatever we can.

Ramsey Russell: Now, that’s becoming a common thing in the last several years, down in the Deep South. The hunting quality seems to have diminished. I hear a lot coming out of Louisiana about that, also, about the hunt quality diminishing. Me, personally—everybody knows my favorite ducks: the ones next to the decoys. Now, if I happen to be hunting somewhere and there’s just a whole bunch of mallards, I might let a shoveler get a pass. The craziest thing I ever did, this year— I was hunting out in California, and there were bazillions, bazillions upon bazillions, of pintail ducks. Limit’s one. We go out to this rice field, me and my buddy John Wills, and, of course, “Bam! Bam!,” we get our pintails right off the bat. Now, we got to sort through other species. Just gazillions of pintails buzzing around, but the craziest thing is: I was finally sitting on duck number six—you can shoot seven in the Pacific Flyway—and John said, “About thirty minutes to go. You ready to go?” I’m like, “Uh-uh. I’m going to wait. I’m going to wait it out. I’m in now. I’m one away from the limit, I’m going to stick it out.” I never will forget; a bald eagle sailed over this field, the next field over, and got all these ducks up. I’m watching this Macy’s Day Parade of pintails coming over. I’m looking at all these beautiful sprigs, and I’m just, “Pass, pass, pass”—and there’s a dang shoveler, right up amongst them. “Boom!” That was my number seven. But it wasn’t lost on me, the fact that I am passing thousands of pintails to shoot a shoveler. But he was in that rice field, and he had a lot of fat on him. Times have changed since Florine Pie Champagne hunted.

Benny Broussard: Yeah. I made one good quality hunt this year. The White Lake Reserve, down south of Gueydon. It’s state-owned— That land was owned by an oil company. They owed them tax money, so they donated like 71,000 acres to the state. It’s a lottery hunt. Well, there’s expensive paid hunts that you can do, that’s with the wealthier people, but the average folks like myself can do a lottery hunt. I’ve been lucky; about every other year I get picked for a lottery. This year, I got to go teal hunting. My boss got picked for a lottery hunt, and he asked me to go with him on a teal hunt. We did pretty good. We got our limit. Then we went in November. I got picked for the big duck season, and me and my son went. Right off the bat, we each dropped a specklebelly goose. Then we were shooting mallards, and then, after a while—they told us they had a lot of pintails at that area, and we hadn’t seen any yet—finally, the first pintails that came in. Like you said, the limit’s only one. I dropped remember picking out a male, and I dropped the male. The blind was like a little island in the middle of a pothole in the marsh, and mine fell on the other side of the blind. I didn’t see it. My son shot a female. Then, later, when the guide went to pick up all our ducks, he found everything but the male pintail. Which, I wanted to have it mounted. I have been wanting to get one mounted. Anyway, he couldn’t find mine. I was upset.

Hunting ducks with grandfather’s old shotguns?

Ramsey Russell: Have you ever shot a duck with one of your granddaddy’s guns?

Benny Broussard: Oh. Well, yes. The one that he won in 1951—that gun was given to my dad. I don’t know if he ever hunted with that gun, but he gave it to my dad. My dad had hunted a little bit before the war, and then after the war. Well, no, he didn’t hunt with that gun because he got that after the war, World War II. But my dad gave the gun to me, which I’ll later pass on to my son. That’s what I grew up with, hunting, was that Remington model 870.

Ramsey Russell: What about that Model 12?

Benny Broussard: I never hunted with that. After I found out about Mr. Dale hunting with these Boss Shotgun Shells, I think I might ask my cousin if I can borrow that Model 12. This coming year, I’d really like to make one hunt. Even if I only kill one duck, I’ll be happy.

Ramsey Russell: I’ll tell you this, I grew up before steel shot. Nobody in the family owned a three inch magnum. We all shot two and three quarter inch, that’s number one. Number two, we found out real quick—just through the internet—when they came up with that steel shot, the talk was, “Don’t put steel shot in the guns you’ve been shooting. It’ll mess up the barrels.” I actually took my granddaddy’s gun out, year before last, and I still took it out this year, I believe. I take it out, and it’s no longer a safe queen. I took it out, and we’re shooting Boss Shotshells’ copper-plated bismuth. Let me tell you what, those guns shoot differently than these modern shotguns. They pattern better and hit harder. Our granddaddies were really good shots, but they had a little bit better hammer to drive a nail with, too. Those old shotguns, there’s something about their pattern. A couple of years ago, I also took out an old family gun: double-barreled Colt Damascus, built back in the late 1800’s. It was my great, great granddaddy’s. And only because of Boss Shotshells—because you can’t shoot lead, no more—I felt comfortable going out and shooting it. I couldn’t miss with that gun. It really shot well. Man, I tell you what—especially knowing that Boss Shotshells will not mess up the barrels, and the way that stuff is constructed, and how it hits, which is pretty hard—heck, I’m dying to borrow the gun and go out and shoot a duck with it, too, having heard about your granddaddy. You know what I felt like? I swear, nobody in the family knew who that double-barreled gun really belonged to. They didn’t know nothing about it. My grandmother even said, “You know, it may have been my granddaddy’s.” But she didn’t know nothing about it, because she didn’t remember her granddaddy duck hunting.

I went and hunted with a friend of mine, up in north Mississippi. It was a terrible duck season, it was slow. He said, “Hey, look, come up here and hunt. We’ll film this. But, Ramsey, it’s a terrible duck season. I don’t even think I’ve shot a limit all year.” It was like my ancestors spoke from the grave through the end of that gun, and the ducks just showed up. It was something so rewarding to connect to my ancestors like that, just by taking that gun out and giving it life. You know what I’m saying? There’s something rewarding to me about that. I was curious because I actually came into—my daddy had a Model 12. He and my uncle had both been given one by my granddaddy. When he passed, my brother and I don’t know what happened to it. But I came into one. A friend sold me one, this year. Man, that gun shoots well. I really got a thing for Model 12 shotguns. I don’t know what it is, but I really do.

Louisiana market hunting grandfather Florence Pie Champagne’s influences?

Ramsey Russell: Benny, I know you didn’t duck hunt with your granddaddy, but, obviously, you grew up your whole life—you’re in your sixties—you’ve heard your whole life from your mama and your uncles and all your folks about your granddaddy. I know you’re very proud of him. Just the stories you got, and the memorabilia. How do you think he might have influenced your life and your way of duck hunting?

Benny Broussard: I know he definitely was an influence. Because, like I said, my dad was a duck hunter, but when he came back after World War II he didn’t want to hunt anymore. So, listening to the stories about my grandfather, I’m sure that’s why I’m a duck hunter, today. Because of my grandfather. I just admired him, the life. I used to just live to hear those stories. From him, from his son Paul, from my mother and all the other siblings.

Ramsey Russell: I never duck hunted with my granddaddy. We went dove hunting, some, but I never duck hunted with him. He was that generation; he didn’t take children to duck camps, or to duck blinds. He had retired. His health failed him before I was old enough to go the duck blind with him. We did go to duck camp, some, during the summertime, workdays and stuff like that, but we didn’t really go out and duck hunt. I never shot a duck with him. But his stories. His story. I’ll never forget, I grew up deer hunting. Doing that kind of stuff. I was down in Texas working on a deer ranch, wanted to be a deer biologist, and there were a bunch of ducks on some of them stock tanks with thirty miles of padlocked gate. I went out one morning—no decoys, no call, no nothing. No real formal background in it. I just sat quietly, and a duck got up and flew. I shot, and a bunch of them got and rallied around. I filled up croker sack with them, and just that connection—that act—and my granddaddy’s stories made me a duck hunter. I can’t get enough of it, to this day. It influenced me, his stories and his presence. Never shared a duck blind with him, but I heard those stories. I’m assuming it was the same way with you.

Benny Broussard: Yeah. Sure was.

Ramsey Russell: Sitting on his front porch while he’s tying those cast nets, you would hear these stories from him.

Benny Broussard: Yeah. Sure would.

Ramsey Russell: Do you have a favorite story? Can you reach back in the memory bank from a long time ago? Do you have a favorite story, or just a favorite memory, of your grandfather?

Benny Broussard: He did talk a little bit about the market hunting days, and a little bit about the skeet shooting, and things like that. Most of the stories came later, from Paul. I did get to actually see him shoot, one time. Actually, somebody had bought him a little BB gun. A little Red Ryder BB gun. I was pretty young at that time, and, you know, being a kid, you’re curious. You see the gun in a closet or something like that. I was always digging around in the house. I asked about the gun. He said, “You want me to shoot you a bird?” I said, “Yeah.” He walks out on the porch—well, he could barely walk, he walked with a walker—and he leaned up against the railing. There was like a pecan tree. It seemed like it was about eighty foot tall. A little sparrow, at the top of that tree. He shot that sparrow. It fell dead. One shot. Told me to go get it. I brought it back to him, and it was hit right in the head. And that’s a little BB gun. Yeah, these little Red Ryders are not accurate guns. I was just really impressed that somebody could hit something like that.

Ramsey Russell: I would have said they weren’t very accurate, either, but maybe it was the Indian, not the arrow.

Benny Broussard: Could be.

Why Was Florine Pie Champagne Most Famous Market Hunter in Louisiana?

Ramsey Russell: I got one more question. I just got to ask this. What do you think made your granddaddy, Florine Pie Champagne, the most famous market hunter in Louisiana?

Benny Broussard: It had to be his shooting skills. Definitely his shooting skills. He was just an incredible shot. Uncle Paul said it was his eyes. He just had these incredible eyes, and he just had the knack for shooting.

Ramsey Russell: Did he speak French?

Benny Broussard: Oh, yeah. He was French. Definitely French.

Ramsey Russell: When he talked to you, when you were fifteen years old, was it mostly French?

Benny Broussard: No. Well, he had a pretty heavy accent. But, no, he didn’t speak mostly French. It was in English where I could understand him. Now, on the Broussard side, I had one grandmother that only spoke French. I never could speak to her because we didn’t learn French. The three older children in my family learned French, but me and my two younger sisters never learned French.

Ramsey Russell: How did he pronounce his last name?

Benny Broussard: It was Champagne (shaam-pine). Florine Pie Champagne.

Ramsey Russell: Florine Champagne. But everybody called him Pie.

Benny Broussard: Pie. Short for Pious.

Ramsey Russell: Folks, y’all have been listening to an incredible story about Louisiana’s most famous market hunter, Florine Pie Champagne. Thank y’all for listening to this episode of Duck Season Somewhere. We’ll see you next time.