Press Room

The Greentree Reservoir Management Dilemma

The following paper was written about 30 years ago while in graduate school at Mississippi State University, but is as relevant today as ever. Never more so than in Arkansas, where flooded green timber is synonymous with public land hunting. Wildlife habitat managers are facing a true dilemma. After many years of mismanagement due to antiquated or poorly designed water control structures, the health and vigor of bottomland hardwoods with state and federal greentree reservoirs have declined greatly. Advanced regeneration of southern red oak species–those species that produce nutrition for wintering waterfowl in the form of acorns–is necessary to ensure that this component exists in the future. There’s no quick fix. As described in the link below, timber thinning (to increase sunlight) and dry seasons (to mimic site-specific hydroperiod) is required. That takes time that’s measured in years, not weeks or days. Consequently, what are we waterfowl hunters to do? Where shall we hunt during the interim? Do we destroy these bottomland hardwood habitats for our own self interests or make sacrifices for future generations?

Greentree reservoir (GTR) management is a strategy that typically consists of impounding a bottomland hardwood stand with levees and seasonally flooding the living hardwood trees to provide waterfowl habitat (Wigley and Filer 1989) and to enhance timber production (Newling 1981). Landowners near Stuttgart, Arkansas, initiated the practice during the 1930s solely for the purpose of enhancing waterfowl hunting opportunities on their property (Hunter 1978).

An estimated 80% of Mississippi Alluvial Valley forested wetland acreage has been lost to agriculture and human development (Baldassare and Bolen 1994); hence, GTRs play an increasingly priceless role in migrating and wintering habitat for waterfowl, particularly mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) and wood ducks (Aix sponsa). Waterfowl obtain carbohydrate‑ and protein‑rich forage from these habitats (Heitmeyer 1985, Wehrle et al. 1995). Forested wetland structure also affords waterfowl sites for cover, refuge, and behavioral activities (Heitmeyer 1985).

Most GTRs are flooded only during the fall and winter dormant season, and increased woody stem growth has been demonstrated. Recent studies of GTRs have shown, however, that consistent flooding during the dormant season for many years may decrease mast production and adversely affect growth rates, vigor, and regeneration of timber. There is convincing evidence that current GTR management practices promote a shift in vegetation towards more water‑tolerant species (Newling 1981, Young et al. 1995) and increase problems with water stress in red oaks (King 1995, Young et al. 1995). Therein lies the GTR management dilemma: both diminishing waterfowl habitat quality and decreasing productivity of commercially valuable hardwood timber may be an end result of otherwise well‑intended management efforts.

Read More: The Greentree Reservoir Management Dilemma: A Literature Review (Russell, 1996)

Anti-Hunting Politician Accused Donald Trump Jr. of Shooting a Protected Duck in Italy

Anti-Hunting Politician Accused Donald Trump Jr. of Shooting a Protected Duck in Italy. A spokesman for Trump Jr. says he was not hunting illegally or in a protected area, and that he will cooperate with any investigation into the take of a ruddy shelduck.

International and national media outlets are having a field day after an Italian politician claimed Donald Trump Jr., the eldest son of President Trump, killed a “very rare” duck on a hunt in Italy. The accusation stems from video footage posted Tuesday to the Italian media sites like Corriere Della Sera that shows Trump Jr. running a shotgun and sitting in a brushed-in shooting hole with ducks piled in front of him.

Budget Would Clip Bird Banding. Hunters Not Happy.

For more than a century, the Bird Banding Laboratory has placed small metallic bands on the legs of birds across North America. Each year, the lab receives thousands of reports from bird watchers and biologists who spot the markers on the birds and report them to the lab. In this way, the lab tracks and monitors the movements and numbers of birds, from sparrows to sparrow hawks.

For more than a century, the Bird Banding Laboratory has placed small metallic bands on the legs of birds across North America. Each year, the lab receives thousands of reports from bird watchers and biologists who spot the markers on the birds and report them to the lab. In this way, the lab tracks and monitors the movements and numbers of birds, from sparrows to sparrow hawks.

At a moment when bird populations are declining globally, bird banding is essential for conserving species and tracking population changes over time. It is also integral in setting regulations and limits for waterfowl hunting. Indeed, no group reports more bird bands — or prizes them more — than hunters.

The trophy may not last. The lab falls under the U. S. Geological Survey’s Ecosystem Mission Area, the agency’s major ecology program, which under President Trump’s 2026 proposed budget would see funding reduced to $29 million, from $293 million. Many hunters are unhappy at the prospect.

Each band reported by hunters is essential for detecting changes in waterfowl populations and for setting hunting regulations. In its contribution to waterfowl management, the Bird Banding Laboratory “has given us something that is the envy of the world,” Ramsey Russell, a duck hunter in Mississippi, said.

Many birds migrate between Canada and South America every year. To coordinate all of the data, the Bird Banding Laboratory works with the Bird Banding Office in Canada — which could be crippled if the American lab is defunded, said Chris Nicolai, a waterfowl scientist at Delta Waterfowl, a duck conservation nonprofit.

Dr. Nicolai noted that a significant portion of band data is collected, for free, by hunters, who also buy duck stamps to legally hunt waterfowl. The stamps, in turn, support habitat conservation.

Read Full NYT Article: Trump’s Budget Would Clip Bird Banding. Hunters Are Not Happy. The Bird Banding Laboratory has turned duck hunters into citizen scientists. What happens if it is defunded?

Evolution, population structure and morphology of the African Black Duck Anas sparsa and Yellow- billed Duck A. undulata

In addition to the first population genomic assessment of African Yellow-billed Duck and African Black Ducks, we also use morphological features to build out a field key to identify between sexes of these monochromatic species. We demonstrate clear population structure between these two species, and while hybridization rates are near-zero did recover the first confirmed and highly backcrossed yellow-billed x african black duck hybrid. We also provide a field key that is >95% accurate in sex identification when considering mass and bill length only.

In addition to the first population genomic assessment of African Yellow-billed Duck and African Black Ducks, we also use morphological features to build out a field key to identify between sexes of these monochromatic species. We demonstrate clear population structure between these two species, and while hybridization rates are near-zero did recover the first confirmed and highly backcrossed yellow-billed x african black duck hybrid. We also provide a field key that is >95% accurate in sex identification when considering mass and bill length only.

This work would not have been possible without the help of Ramsey Russell who did the diligent work of data and sample collection while in South Africa…so shout out to the research arm of GetDucks.

To cite this article: Philip Lavretsky, Ramsey Russell, Sara Gonzalez, Vergie M Musni, Alexis Díaz & Joshua I Brown (19 Jun 2025): Evolution, population structure and morphology of the African Black Duck Anas sparsa and Yellow-billed Duck A. undulata, Ostrich, DOI: 10.2989/00306525.2025.2509215

Link to this article: https://doi.org/10.2989/00306525.2025.2509215

Netta a Dull Moment: Are The Rosy-bills In?

In pursuing waterfowl hunting’s most coveted trophies, we duck hunters often find ourselves traversing the globe, seeking species that not only challenge our skills but also enrich life experiences. And it’s a mighty big world. It’s so big and beautiful that it’s hard to choose favorites other than “the next one!” But let’s start here. Among my personally favored ducks, the 3 species among the genus Netta—the rosy-billed pochard (Netta peposaca), the red-crested pochard (Netta rufina), and the southern pochard (Netta erythrophthalma)—stand out. Here’s why.

In pursuing waterfowl hunting’s most coveted trophies, we duck hunters often find ourselves traversing the globe, seeking species that not only challenge our skills but also enrich life experiences. And it’s a mighty big world. It’s so big and beautiful that it’s hard to choose favorites other than “the next one!” But let’s start here. Among my personally favored ducks, the 3 species among the genus Netta—the rosy-billed pochard (Netta peposaca), the red-crested pochard (Netta rufina), and the southern pochard (Netta erythrophthalma)—stand out. Here’s why.

Read Full Story: Are The Rosy-bills In?

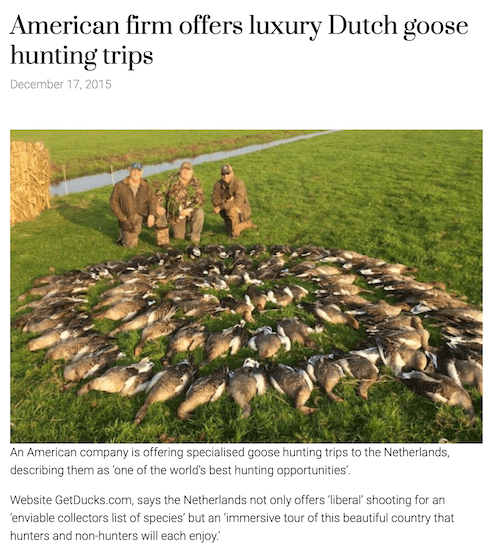

Dutch Goose Hunting: Conservation, Avian Flu and Control

Defending Dutch Goose Hunting: A Hunting Conservationist’s Rebuttal

Dutch goose hunting critics often paint it as needless cruelty, but the reality is that Dutch goose hunting is a pragmatic response to a very real, man-made wildlife crisis. The Netherlands faces an overpopulation of wild geese on an unprecedented scale – a situation created by human activity and policy. Left unchecked, this goose population boom is causing significant ecological and economic damage, endangering public safety, and even raising the risk of avian influenza in the Netherlands and beyond. In this rebuttal, a conservationist perspective is offered: regulated goose hunts are not only defensible but necessary as a form of goose population control and conservation through hunting.

The Backstory: GetDucks.com Netherlands Goose Hunting Trips Ruffle Dutch Feathers

In December 2015, all hell broke loose at GetDucks HQ. It began at 2 AM Mississippi-time (9 AM Amsterdam time). Surly, fast-talking, self-important Dutch reporters with heavy accents were on the other end of the call. Skipping standard perfunctory telephone pleasantries altogether–to include introductions–they bluntly demanded in almost unintelligible “English” instantaneous explanations for “shooting ‘der geese.” By lunch that day, DutchNews.nl had published an article entitled American firm offers luxury Dutch goose hunting trips, painting a sensational picture of American hunters flocking to the Netherlands for “one of the world’s best hunting opportunities.”

Other local and national “news” rags joined in (such as Americans ruffle feathers with unlimited trophy goose hunting trips to Netherlands). The articles highlights promotional language from US outfitter Ramsey Russell’s GetDucks.com boasting of “‘liberal’ shooting for an ‘enviable collectors list of species’” and an “immersive tour of this beautiful country” for hunting clients . Emphasis was placed on the $4,600 price tag for a five-day “luxury” goose hunt package, framing it as trophy tourism exploitation. The articles oftentimes noted that Dutch law technically allows foreigners to hunt if hosted by a Dutch license-holders, implying that “Dutch hunting legislation allows foreign nationals to go on ‘trophy hunts.’” A Dutch Labour MP, Henk Leenders, even raised parliamentary questions, signaling political unease with the idea of wealthy Americans shooting local geese for sport.

To drive home the highly inflammatory “trophy hunting” narrative, DutchNews.nl quoted testimonials of American hunters proudly reporting big goose hauls: “We got 42 barnacle geese … during two morning hunts,” one client wrote, alongside a photo of piled birds. Another bragged, “I think we took 40 geese on the opening day… We’re going back – pencil us in for next August” . These anecdotes, paired with the article’s tone, suggested outrage: the image of foreigners reveling in mass kills of Dutch geese purely for fun. The implication was clear – the Dutch public is meant to see this as a gaudy, gratuitous “trophy hunt” enterprise deserving of scrutiny or scorn.

Whether fearing political reprisals or simply lacking testicular fortitude, even the Royal Dutch Hunters Association–that supposedly champions hunting in Holland–quickly chose sides. Altogether forgetting our previously cordial emails regarding hunting laws in Netherlands, condemning our use of the word “trophy,” and criticizing our goose hunting in Holland altogether, they all the while phished for local names to feed to the jackals while, of course, politically ingratiating themselves to the anti-hunting influences causing the stir in the first place.

Planning for Forest Stewardship: A Desktop Guide

An essential resource for private forest landowners, conservationists, and forestry professionals aiming to develop comprehensive forest stewardship plans. Co-authored by D. Ramsey Russell, Jr., then Refuge Manager at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Tallatchie National Wildlife Refuge, and Susan Stein, Forest Stewardship Coordinator at the USDA Forest Service, this guide provides a structured approach to sustainable forest management.

If you’re a private landowner aiming to enhance wildlife habitat, increase timber value, and ensure long-term sustainability of your forested property, a well-crafted Forest Stewardship Plan is essential.

Planning for Forest Stewardship: A Desk Guide, co-authored by Ramsey Russell and published by the USDA Forest Service in 2002, offers a comprehensive, step-by-step approach to sustainable forest management.

Key Components of a Forest Stewardship Plan:

•Landowner Objectives: Define clear goals—be it wildlife conservation, timber production, recreation, or legacy planning.

•Resource Inventory: Assess current forest conditions, including tree species, soil types, water resources, and existing wildlife habitats.

•Management Recommendations: Develop strategies for habitat enhancement, selective harvesting, reforestation, erosion control, and invasive species management.

•Implementation Schedule: Outline a timeline for executing management activities and monitoring progress.

Global Pursuit Expand Your Upland Hunting World with SCI Gamebirds of the World

It’s been said that the largest armed force on earth convenes on grain fields each September to shoot doves. Under the hot sun, around barbecue pits, iced drinks and panting dogs, camo-clad hunters usher in the real new year pursuing birds.

Fireworks erupt at the legal shooting time. Shotguns blast salutations at diminutive gray gamebirds that streak overhead, barrel-rolling like Top-Gun cadets, some falling in a feathery poof. That’s how my own indoctrination into hunting humbly began under the watchful eye of my grandfather. But the world’s one helluva lot bigger than a dusty Mississippi Delta dove field.

I found out that doves were plentiful in South Texas when I was working there in my college days. I also hunted bobwhite and scaled quail there. They preferred running to holding tight, but they were no match for my energetic springer spaniel. The behavior of those birds was an eve-opener for both of us.

We returned home with our hunting world expanded. We then pursued the migratory woodcocks in bottomland hardwood thickets, Wilson’s snipe on the drained-field mudflats, and moved on to pheasant in corn fields of the Midwest.

SCI Game Birds of the World Awards helps hunters learn about the many opportunities for wingshooting around the world and rewards their efforts. The platform is relatively new and stands alone from SCI existing game species awards.

Registration is as simple as completing a SCI Gamebirds of the World Photo Entry Form and submitting a grip-and-grin photo showing the distinguishing feather characteristics of your prized game bird.

My upland journey continued with deep-woods ruffed grouse, open-prairie sharp-tails and all the overseas birds: black grouse, capercaillie and an entire world’s worth of beautiful gamebirds. It was then on to Argentina, which is renowned for ducks and doves, but where hunting perdiz over pointers speaks to their own traditional heartbeat. Likewise, in South Africa, hunting guineafowl, rock pigeons, sand grouse and myriad francolin species have been elevated to near art form via orchestrated drives and deployed German short- haired pointers.

The world is full of amazing gamebirds. The awards program helps ensure hunters on their journeys know of these many opportunities for sport and conservation around the world. Check out safariclub.org/game-birds-of-the-world to get your journey jumpstarted.

And to think that my journey with the gamebirds of the world all started on a dove field in Mississippi.

SCI Gamebirds of the World Awards Platform Opens Exciting New Frontiers

Backdropped by the mountainous game room displaying world sheep slams and other lifetime accomplishments from hunting big game worldwide, devoted Safari Club International (SCI) member Shaun Harris explains, “I’ve always loved hunting ducks and upland birds, but there’s something about their subtle beauty—about their dazzling colors, especially—that add another whole dimension to this room where I’m reminded of some of the happiest times of my life. And a lot of hunters don’t even realize that birds can be hunted nearly anywhere worldwide that big game are hunted.” The world truly is a whole lot bigger than our own back yards, abounding with dizzying arrays of ducks, geese, swans and upland gamebirds worldwide. In fact, there are 6 whole continents worth of opportunity!

Water runs downhill, collecting in low-lying wetlands. For that reason alone, waterfowl are most oftentimes hunted worldwide at or even below sea level. But that’s where things get fun—based on a 100-plus species’ varied life histories, chasing them takes hunters to open seas and rocky shorelines, fast-moving rivers and tranquil marshlands, all points in between. Great needle-in-a-haystack example of fully immersing oneself into a landscape while toting a shotgun and wearing waders is hunting African pygmy geese. In an otherwise arid, South Africa landscape, they’re hunted in lily pad-covered wetlands. Talk about fresh perspective! And there are exceptions to the low-lying areas rule, too—such as the unique ducks and geese inhabiting high-altitude, altiplano wetlands among the Andes Mountains.

As if waterfowl weren’t enough to keep us busy, there are 100-plus more upland gamebirds. While hunters may have since progressed up hunting’s food chain, most youthful hunting introductions likely involved swinging hand-me-down scatterguns at doves under the watchful eyes of their ancestors or stumbling headlong through cover behind setters that behaved way differently with noses full of birds than when they’d been asleep under the kitchen table the previous night. To later learn there’s a world full of such gamebirds can be eye-opening. And inspiring. Stalking capercaillie in boreal forest environments so quiet that breath can be heard crystallizing, watching driven guineafowl hurling towards the shooting line like black-with-white-polka-dotted cannonballs, seeing ruffed grouse fading from peripheral vision more quickly than a shotgun can be shouldered embodies addictive explorations of new feathered frontiers seeped in deep-rooted upbringings.

SCI’s Gamebirds of the World Awards Platform is a relatively new, standalone platform not intermixed with existing Big Game Species Awards. It will increasingly bring needed attention to bird hunting opportunities and conservation. Registration is as simple as completing a Gamebirds of the World Photo Entry Form and submitting a grip-and-grin photo showing distinguishing feather characteristics of your prized gamebird.

SCI has forever been the world’s foremost advocate of hunting and wildlife conservation, but the new gamebirds platform opens important new frontiers. For longtime members that have completed their big game quests or are looking for new adventures to complement their big game hunts, hunting gamebirds will be like finding religion. Importantly, expanding our renowned record book program to include waterfowl and upland gamebirds will potentially attract a newer generation of hunters that are passionate about what SCI represents. And this comes at a time that the stakes have never been higher.

Cape Barren Goose bucket list fulfilled

Ramsey Russell is the owner of GetDucks.com, a United States-based company that facilitates duck hunting experiences worldwide and has been doing so since 2003.

He has hunted on six continents and spends about 225 days a year pursuing his passion, which has allowed him to gather a wealth of knowledge from around the world including during multiple visits to Australia, where he has hunted with Field & Game Australia members and also helped with waterfowl research activities. This passionate waterfowler has hunted diverse species in some truly amazing locations, but after two decades in business there are still some “bucket list” birds and experiences on his radar, hunting Cape Barren geese foremost among them.

Here, Ramsey Russell gives us an insight into a trip he made in January this year, leaving his Mississippi home and the North American winter to spend a week hunting Cape Barren geese on Tasmania’s Flinders Island.

Long journey worth the effort

“Five flights later, the shimmering Bass Straight was glimpsed through puffy clouds, and ahead lay the small Flynder’s Island that was our destination,” Ramsey said. “Covering roughly 550 square miles, it’s inhabited by 900 people living close to the land. No [crazy] Australia anti-hunters here, I was told … no crime either. Cows and sheep plentiful, Cape Barrens too.”

Ramsey said the birds evolved in brackish marshes and still bore the greenish-yellow cere to excrete salt – but had since adapted to the island’s abundant pastureland – He said other distinctive features of Cape Barren Geese are their talon-like claws on deeply lobed webbed feet, and heart-shaped dark spots on their feathers. “Highly territorial, pairs and cohorts stake out each paddock across the landscape as their own,” he said. [Read More: Cape Barren Goose bucket list fulfilled]